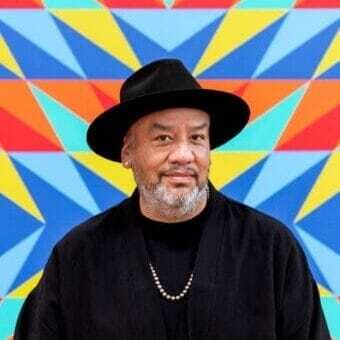

by Cory-LaNeave Jones

June 25, 2025

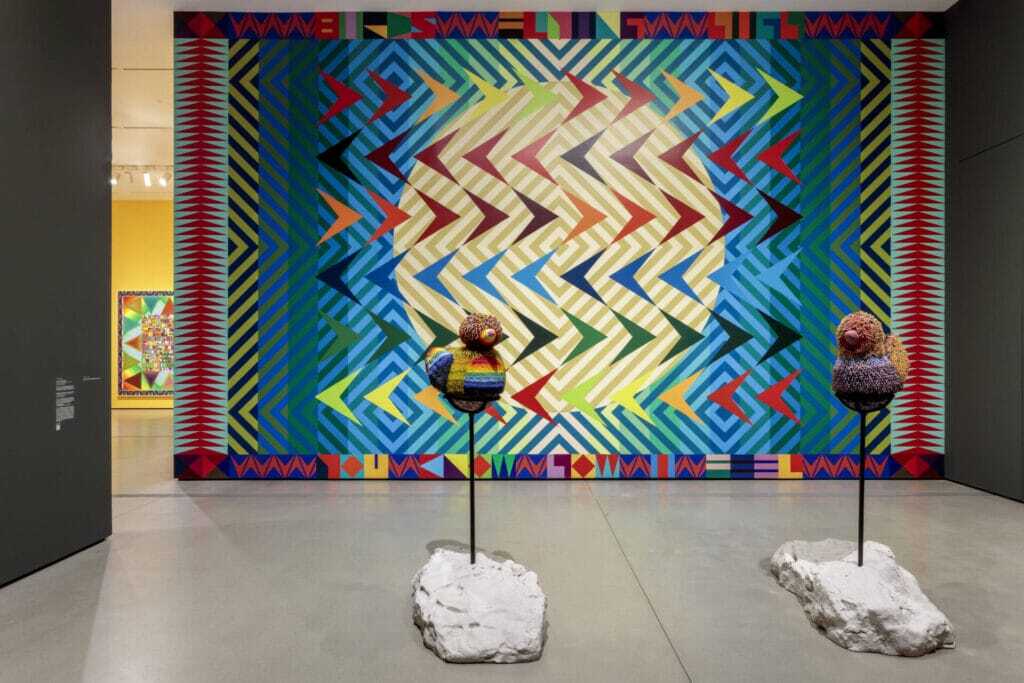

Jeffrey Gibson has brought his fabulously bright and kaleidoscopic exhibit all the way from the Venice Biennale to Southern California. Jeffrey Gibson: the space in which to place me is on view at The Broad in Downtown Los Angeles, now until September 28. This is a NOT-TO-MISS show.

“Okcha” is the Choctaw word for “Awake,” or “Wake Up.” Perhaps an apt word for the times in which we are living: we must keep our eyes peeled and learn to experience life exactly as it presents itself to us. Jeffrey Gibson was the first Native American artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, what Artsy has called “the world’s most important art exhibition,” which highlights artists from across the globe every two years.

While many communities are still in serious discussions about the repatriation of goods and land to their original owners, the show is timely given the current federal administration’s removal of diversity, equity and inclusion from their federally-funded American diction.

Jeffrey Gibson said “this exhibition, I think, will in many ways fulfill some hope that people are looking for during this time. It’s a really challenging time for institutions. It’s a challenging time for artists. I would like to say that we all feel unified by the challenges of this time.”

the space in which to place me is an exhilaratingly colorful exhibition that incorporates every color in our visual spectrum as well as important documentation and context about the Native American experience.

The title of Gibson’s exhibition, “the space in which to place me” is adapted from a poem written by a Oglala Lakota poet named Layli Long Soldier. That poem “Hé Sápa” is literally written around a block-shaped space.

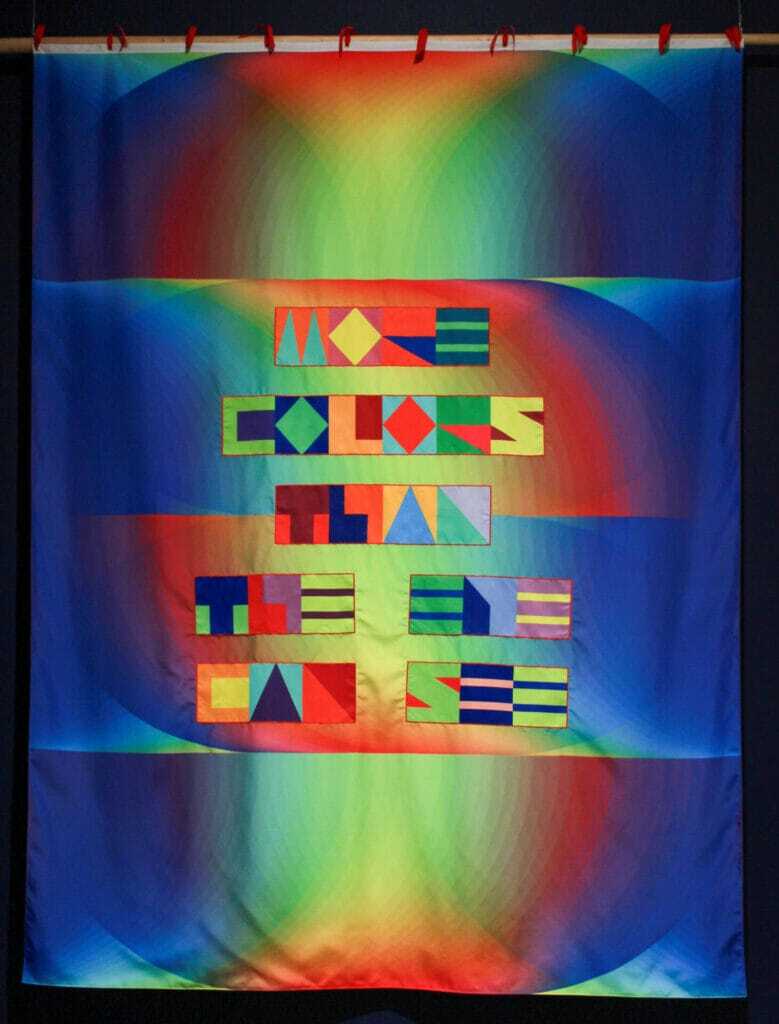

Jeffrey Gibson’s work celebrates the brilliance and multiplicity of the visual spectra such as in the piece titled “More Colors Than The Eye Can See.” In some ways they also serve as a visual archeological exploration. Just as digging into the sediment can uncover artifacts and information from generations past, this exhibit taps into the layers of the Native American experience.

According to the ancient Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) philosophy, the Seventh Generation Principle states that “decisions we make today should result in a sustainable world seven generations into the future.” Seven generations ago, or about 150 years ago, in 1875 LA was just a small village of about 5,000 people and by 1900 there were 100,000. Today, LA hosts 3.8 million people. The City was El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles and was originally “established” (perhaps we should just say designated as a place thence known to the non-indigenous peoples) in 1781. At that time there were estimated to already be 5,000 native Tongva people in the LA basin.

In the opening of the exhibition, two other natives from Los Angeles, Lazaro Arvizu Jr. and his mother Virginia Carmelo (both Tongva, Gabrielino) were present to acknowledge the space of this beautiful exhibit as originally tribal land and to welcome both Jeffrey’s work and all those visiting to acknowledge the centuries of presence of the Tongva peoples within the Greater LA Basin. Lazaro played a beautiful piece on a wooden flute that was accompanied by sounds of nature.

“We are among over 100 native California tribes lacking the status of federal recognition. The ancestors said that we have always been here” Virginia Carmelo stated. “More than 40 years ago, when I began to get invitations to share a little bit about our people here, I was told by the archeologist and anthropologist at that time that we had been here 3,000 to 4,000 years. Later on, in the early 2,000’s with the incoming of studies of DNA, we were told that we have been here 9,000 years. Last year, working with the Natural History Museum here in downtown Los Angeles, they are telling us now, we have been here at least 13,000 years. That’s the ice age. So, I believe what the ancestors told us, we have always been here.”

…

Carmelo also presented an abbreviated history of the Tongva peoples and spoke the correct pronunciations of several locations I had heard of:

…

“We had the village that we call Yaanga. … Our Tonvga tribal ancestral lands cover the entire Los Angeles basin and the four Channel Islands. We identify this today as the greater parts of Los Angeles, Orange and parts of Riverside and San Bernardino Counties. We are bordered by the Santa Susana Mountains, the entire San Fernando Valley was home to many Tongva villages, Tuxunga, Kawee’nga, Pakiynga. You might recognize these as Tujunga, Cahuenga, and Pacoima. … And to the south we have the natural creatures and boundaries of today’s San Joaquin Hills, Santiago Canyon, and all the way to Aliso Creek. I come to you today from Hotuuknga which you may know as Anaheim on the West, we have a coastal village, one of them being Topaa’nga. And you know this as Topanga. And also we have of course our four beautiful islands, the largest Pimu, which you know as Santa Catalina Island, the ancestors identified villages by their significant features of the area. The village name demonstrates that the people have a deep knowledge of their land. We are proud that Kawee’nga is and has always been a flourishing center of abundance and creativity.”

…

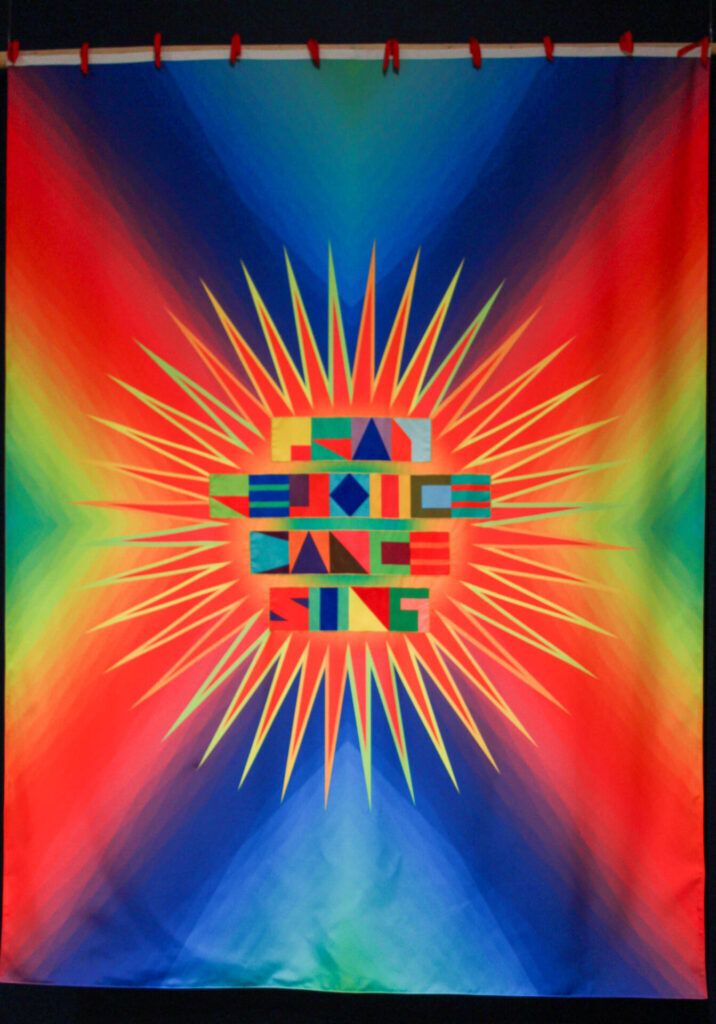

Patterns are important in art. Patterns can represent feelings or rhythms, but they also can express language. Tribal patterns in parts of Africa use patterns as symbols for language. You may have seen such patterns such as the adinkra and kente from Ghana, the bogolanfini from Mali, or the Ankara on the Dashiki outfits or a set of bongo or Djembe or Conga Drums. Both drums and clothing patterns provide stories and rhythms. These are tools that initiate sounds that move our feet, and call to our ancestral serenades. Singing. Dancing. Drumming. Laughter. Love. That is the music of culture. You can hear the indigenous culture in the intricate patterns and rhythms of Jeffrey’s work.

Music is also interwoven into the text within Jeffrey’s work. Citations include lyrics from Tracy Chapman, Mahalia Jackson, Roberta Flack, and Nina Simone.

Written history can also be found in Jeffrey Gibson’s two- and three-dimensional art works. Just as in Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Soloman, which presents a journey of people wishing to grow wings to fly back to the spaces from whence their people came, Jeffrey begins the exhibit’s journey with two birds and the giant words that were famously summoned by Nina Simone in her 1965 hit “Feeling Good.”

While the show provides multiple opportunities for joy and celebration, it also brings forth important documents and contextual information to give the viewer the necessary layers to take it all in. J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur was a first to write about the everyday aspects of early settlers in his 1782 “Letters from an American Farmer.” He was a first to describe the positives and the negatives, including the horrors inflicted upon enslaved peoples. He also popularized the fact that so many different communities from Europe were successfully cultivating the lands in America.

The “trail of tears,” or forced displacement of “the five civilized tribes” including the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole was propelled by the U.S. Congress’ passing of the 1830 Indian Removal Act; this was a time, not of celebration, it was one of the most tragic and horrific periods of our colonizing past.

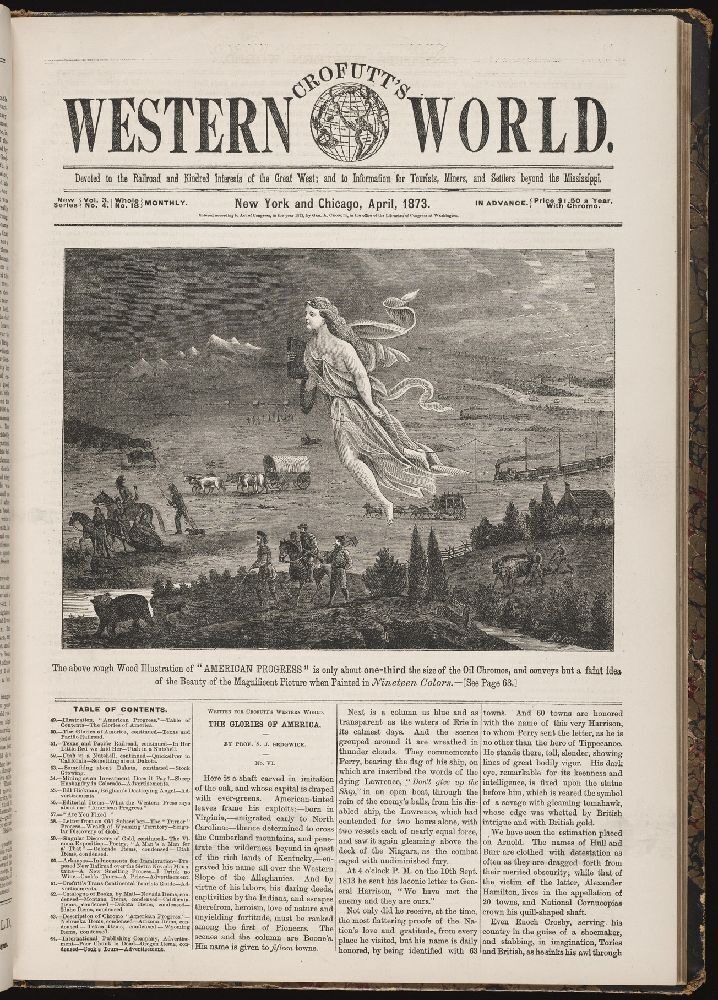

Artists of that period, such as John Gast, were commissioned to create art that promoted the ideas of Manifest Destiny in the 19th Century by demonizing the indigenous peoples and celebrating the overrunning of this land with European cultures. We can now clearly see the false narratives of Crofutt’s Western World. The publication sold itself under the masthead “Devoted to the railroad and kindred interests of the Great West; and to information for Tourists, Miners, and Settlers beyond the Mississippi.”

Jeffrey’s work speaks to me about the giant vibrating steps of mankind moving towards peaceful discussions with one another, yearning to become equals in heart and mind. The foundations of our Constitution emote this vivid truth. The truths that we hold self-evident, … life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In current political times, access to these rights may be argued, but these are the goals of most humans.

The 1st amendment to the Constitution states the following:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

According to the June 2025 Harper’s Index, there are five bills currently being presented to the US Congress intended to restrict the right to peaceably assemble. The Index also ironically notes that four fifths of Republicans believe that Americans should have the right to protest. Perhaps, if only for their causes?

This is where encountering diverse voices and stories deeply matters. In the early 20th century, Austrian-Israeli philosopher Martin Buber suggested that meeting “the Other” in dialogue presents us with what he termed the “I-Thou” and “I-It” relationships. And through these meetings, ethical responsibility emerges from contact with others. And by deduction, this creates the necessity of diversity to provide understanding, empathy, and love.

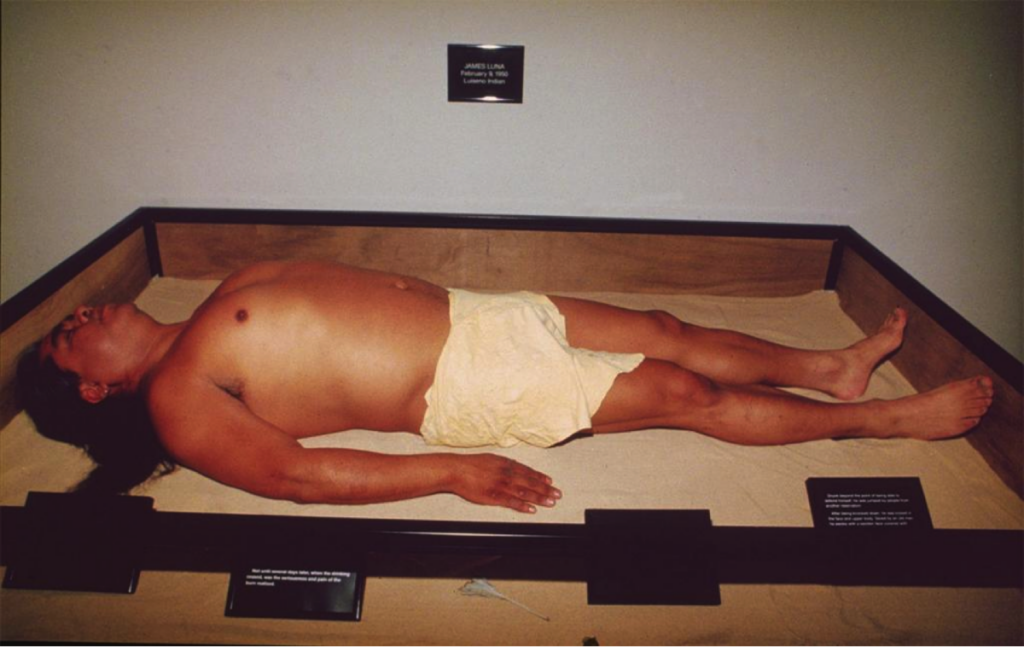

Even with the best intentions however, there is always the danger of mischaracterizing the content or misdirecting the interaction between the art and the viewer. Not too long ago for example, San Diego artist, James Luna was the first to critique the presentation of Native Americans as artifacts of the past. As a performance-piece in Balboa Park, he rested calmly behind glass to present clearly to visitors how indigenous people felt when visiting exhibits about their cultures at “natural history” museums. In both Venice and in Los Angeles, Jeffrey Gibson teamed up with indigenous Native American communities to ensure clarity and authenticity.

–

Joanne Heyler, the Founding Director and President of The Broad said…

“We’re so proud to bring this history making exhibition to LA extending a journey which began last year. This project represented the United States in the 2024 Venice Biennale, where Jeffrey was the first indigenous artist to present a solo show in the US Pavilion. Now, “The Space In Which To Place Me” has traveled over 6,000 miles to come to its home continent. And by being here, the show also marks another first, which is the first solo museum exhibition debut of Jeffrey’s work in Southern California.

This exhibition offers the wide-angle view that stretches from indigenous histories to foundational US documents and contemporary lived experience and intersections of all of those things and more. The works in the show resist the erasure and marginalization of indigenous and many other communities by being irresistibly joyous. The show’s viscerally, exuberant colors drawn from many indigenous aesthetics and traditions, claim space, and I would argue induce endorphins.

Its images and words drawn from quotes from civil rights activists, poems by indigenous authors and pop song lyrics among other sources insist on truth. This exhibition was not created in response to our very specific and current moment, but since it completed its run in Venice last November, its relevance has only intensified at a time when too many communities are facing renewed violence, threat and separation.”

Sarah Loyer, the curator of this show, held a brief discussion with Jeffrey where the themes highlighted the duality of the American cultural history and it’s relation to native peoples and others who have been oppressed over the last 249 to 533 years as well as the duality between the joyous colors used in the work contrasting the divergence of joyousness in “this American life.” Gibson’s work is rooted in both personal identity and heritage. He chooses to present vibrant color, music, and dance to celebrate resilience, joy, and self-expression as opposed to adversity. Incorporating found text and historical references, this work engages with the complicated legacy of oppression and resistance.

Sarah Loyer:

“In 2019, you received the prestigious John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship Award, commonly known as the Genius Grant. And this fall in September, you have been transforming the Mets Fifth Avenue Facade in New York with four new figurative sculptures for the museum’s Genesis Facade Commission. …

representing the country as an indigenous person, as a member of the LGBTQ(IA)+ community, as you were working on this project, how did you begin to think about that complex position? How did that thinking change over time and turn into the exhibition that we see here today?”

Jeffrey Gibson:

“We’re always using this word inclusive, and I just think I thought about has that really been, yes, inclusive is a part of what my modus is, right? But also it’s reflective and I think that I’m telling my story, which is kind of a collaged hybrid narrative of how I’ve become who I’m today. But I truly believe that everyone sitting in this room has their own version of that. So, I think when I think about art making and I think about, well, what do I know best? What I know best is my story, but I also I have to trust that my story is reflective of everyone else’s and some version of it. When I was selected for Venice, I did change my proposal because I realized I was going to be showing it to an audience that was international and may not be familiar with a lot of the conversations around identity and Native American histories here in the U.S.

…

My story is American. My story is as a gay man. My story is as Native American and specifically coming from the origins of the southeast of the United States. So I think it was really just trying to be true to that story. And there’s a lot of trust that happens. I think during the run of the exhibition. I think that things like color, things like music, things like dancing, these are all things that all of our originating cultures share at some point. And so even if people don’t talk about ’em on a daily basis, many of us know those stories from our grandparents or from our great grandparents or from our genealogy that we’ve learned about.

…

I think you do have to trust on some level of the viewer. I always love to think that viewers are much more intelligent than we give them credit for. I think that people are smart. I think that people generally, believe it or not, and it’s a hard thing to say right now, but I do think people like to do what they believe is right. I do like to believe that we inherently have a kind of moral compass of knowing when something is right versus something is wrong. And so in many ways it was, and I’m a child of the eighties and I’m a child of the nineties, and I think the early beginnings of hip hop culture really, and for me and then house culture being so much about an interracial-multiple-identity-community of coming together in spaces of joy, of providing each other safety, I have yet to learn anything better than that. So I will always put that forward.”

…

Sarah Loyer:

“So this exhibition takes a long view of history and while showing how art practices can be forms of resistance and resilience at the same time, this is evident from the very first gallery that visitors will enter, which you can see behind us here with the two bird sculptures. The behind the birds is a mural, and the mural is titled Birds Flying High. You know how I feel, I think everyone recognizes those lyrics from the song popularized by Nina Simone in 1965.

And I think it’s a way of setting the tone for the show. We can think of that song as it’s about finding joy in the little things, finding meaning and joy in the every day, and also doing that despite the social and political struggles one may face, and perhaps even as an antidote to the feelings of hopelessness that those kinds of struggles can provoke. So the work in the show is also frequently using found text and from foundational US documents to civil rights activists, activists statements and poems and engages legacies of indigenous makers, including the title of the show, which comes from Long Soldiers poem, Hé Sápa. And can you tell us about that choice to center resilience and joy and hope in these works? And how does that choice connect to your wider practice?”

Jeffrey Gibson:

“I mean, I don’t know why anybody would choose anything other than resilience, hope and joy. I think the thing that you really want to know is that you always want people to know that they have choices, right? Even in the most dire situations. I think once people believe that they don’t have a choice any longer, that’s really the beginning of the end.

I was raised to believe my mother (from Mississippi) and father (from Oklahoma) [both] come from the southeast… and, they grew up in a time period [with] such extreme racism, violent, aggressive racism. And when I remember my grandmothers, my grandfather’s grandfather, even under those situations of always exercising choice for them, sometimes that meant making a dress that made them feel good. And they made, my grandmother made that dress for the rest of her life.

She (was) just making quilts, making food, prayer, a song, growing food in the garden, fishing, making baskets like practicing medicine, making medicine for protection, any of these things. I think what I realized were counter to the stories of trauma that so many people expect to hear from communities of color looking at that time in history. And I remember there was still love.

There was still babies being born. There was still marriages, there was still celebration and dancing and prayer and worship. And those are the things that I think that’s a choice.

And so I think for me, my use of color, for instance, which oftentimes comes up, I have the most abundance of choice when it comes to color. And the more you learn about color, the more you work with color, you realize that the only way to move forward is in the multiplication of color.

It’s in the understanding the simplest, most subtle nuance of color. You go from one color to an infinite number of colors by your own choice and by your own making.

I think with native histories, aesthetic histories, material histories, realizing when I was in college, how little they were represented in what was happening in contemporary art at the time I realized, wow, I get to be the steward to make people aware of the diversity of Native America. And that became something that became both a responsibility and certainly you want to do it with a degree of ethics, but also in conversation with native communities. But really, we still have yet to scratch the surface of how diverse Native America really is.”

…

Sarah Loyer:

“The flags are hanging vertically inside the galleries and you can see them in their entirety and the entirety of their designs. And they are accompanied by a monumental sculpture, a bronze that was made of the turn of the 20th century by the artist Charles Carey Rumsey titled “The Dying Indian.” In 2019, you made an intervention to that sculpture by commissioning moccasins made for the sculpture to wear, for the Bayport sculpture to wear by the Cree artist, John Little Sun Murie. Can you talk about your intentions with that intervention and why you felt this work would be a powerful addition to the exhibition here in Los Angeles and more broadly at home in the us?

Jeffrey Gibson:

“I mean, I’m not sure how many people are familiar with this kind of sculpture. I mean, the most famous one was the end of the trail. And I’ve talked about the sculpture many times because it also was embraced by many native communities to describe veterans missing an action.

And so I always questioned this, and then the more I looked into it, it’s really like its own genre of turn of the century sculpture, this kind of envisioning of the demise of indigenous people in this continent.

And so I’ve always thought about, well, do I raise his body up? Do I make the sculpture so he’s in a sort of an engaged, active position. And when I saw the sculpture at the Brooklyn Museum, I thought, let’s bring it indoors. Let’s address this. And I was already, in my mind, had the lyrics, the Roberta Flack lyrics, “I’m going to run with every minute I can borrow.”

A number of things within their (The Brooklyn Museum) collection that showed the last buffalo hunt, that showed different ways of indigenous people engaging in indigenous living.

And so I was trying to think what I could do, and I contacted John Little Sun Murie and I said, would you consider making a pair of moccasins?

And what he did, it totally transformed the posture of this figure. And I really consider myself a collage artist.

So that monumental sculpture became just a collage element for me, and really to transform it was the moccasin for it to come on. I think with the way it works here with the flags in Venice, because of the way the flags were hanging, you couldn’t really read the text on ’em.

And this is all text that I drafted, and here to go to your point, Joanne, it really feels so relevant. The text, and you’ll be able to read them here, but not only in relationship to the sculpture and to that history of envisioning the demise of indigenous people, but really they all come across very much as calls for hope, for action, for all of us collectively, for all of us facing challenges today.”

…

The Broad brought in native dancers on the second day after the show opening. This is reflective of a video piece titled “She Never Dances Alone” (2020), a nine-channel video installation, in the work where Jeffrey worked with a native dancer, Sarah Ortegon HighWalking, and also with a native band that infuses hip hop and trance dance into native rhythms with the band known as The Halluci Nation and playing Northern Voice (2 min. 50 sec.) The DJ references A Tribe Called Red – which alludes to a famous hip hop group from the 90’s ATCQ. CLICK THIS LINK and scroll to the bottom of the page to view a snippet of the video piece:

In a song called “The Virus,” the Halluci Nation featuring Saul Williams and Chippewa Travelers, references both a thick connection with family and the need to be awakened:

The people

The women and children were separated from the men

They’re divided as a foot into the regional filters of their minds

The violence of arrogance, crawls into the air, nestles into the geospatial cortexWe are not a conquered people

Drum beats by region

I was awakened by my elder brother

Embracing the messages beautifully presented in Jeffrey Gibson’s artwork, we can imagine a world where better dialogue has the ability to guide us towards a time when we can all come together to all pray, sing, and dance together.

I highly recommend taking one day of your summer vacation this year to celebrate America by driving up to LA and visiting this spectacular exhibit that reaches into your soul and connects you with life, is full of color, and representative of all of the beauty of humanity. Also, be sure to visit the main galleries at The Broad, where you can see wonderful works by some of the most intriguing contemporary artists of the last 100 years, such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Cindy Sherman, Takashi Murakami, Robert Therrien, Keith Haring, Jeff Koons and Yayoi Kusama.

The Broad is located at 221 S. Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012. There is expensive parking along the corner of the building on the south side of W 2nd Street, just west of South Grand Ave. I recommend looking for parking a block or two over off of South Hope Street, that’s where I park when I visit The Broad, MOCA Grand, Walt Disney Concert Hall, LA Opera, or Center Theatre. They are all right there.