By Cory-LaNeave Jones

“Does the infinite space we dissolve into, taste of us then?”

—Rainer Maria Rilke, The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. Stephen Mitchell, NY, Vintage International, 1989.

Artists, philosophers, and theoreticians are often concerned with liminal spaces. Once upon a time, Paul Klee also said that “a line is a dot that went for a walk” in his Pedagogical Sketchbook. Upon another time (1915), Robert Frost pondered which path one should take upon a divergence in a yellow wood. A certain random walk could conjoin such separate paths, but the limits there between are the thing that both Leibnitz and Newton explained in their divergent yet essentially similar thoughts on defining mathematical calculus—that a shape is experienced in two or three or more dimensions. From a mere scientific viewpoint, one could use an instrument, such as a microscope, or scanning electron microscope, or a smaller scope to find the limits of things, or the space between the limits of things, be that the molecular level, the atomic level, or the subatomic. And at some point, you may ponder if any thing actually ever “touches” any other thing.

Heidegger was preoccupied with the thought of things and presence and what he called Being with a capital “B.” An existentialist is most curious of what it is that defines what it is that makes us us. Heidegger called this Dasein (German for Being There).

Sculpture is an artistic means of representing things in space, by both shaping things within the space that we can visually see, manually touch, auditorily hear, breath in what you smell, or taste the minerality, vegetal-ness, umami-ness, sourness, or sweetness of earthly media. Our senses bring us both presence of place (scientific) and presence of relative relation to others (things and or other thinking Beings). Chillida was adept at presenting the tools of the sculptor to reflect and shed a light on our presence in this world and our understanding of ourselves in relation to our world.

The night that sculptor, Eduardo Chillida knew that space was not absence but density: iron cooling into black light, wind pressing itself into stone, space refusing to remain empty. His sculptures do not stand in space so much as persuade space to confess itself. In San Diego—far from the Basque coastline yet uncannily aligned with its horizon—Eduardo Chillida: Convergence unfolds as an exhibition not of objects but of encounters: between matter and air, labor and lyricism, philosophy and the hand.

Rachel Jans, curator at the San Diego Museum of Art, guided Vanguard Culture not through chronology but through what she called “a conversation between the pieces,” one that also “allows us to really enjoy the space that Chillida is articulating.” What emerges is not simply a retrospective of a modern master, but an ethical proposition: that art is a way of letting the world be perceived anew—not dominated, not consumed, but encountered.

If you have time before February 8th, I implore you to visit the San Diego Museum of Art in Balboa Park and experience this convergence firsthand. What follows are the highlights of my discussion with Rachel Jans at SDMA, followed by a deeper reflection on an exhibition steeped in philosophy, material intelligence, and existential inquiry.

Top 10 Elements in Eduardo Chillida: Convergence

- Material as collaborator, not tool (iron, wood, alabaster, clay)

- Space as living entity, not empty container

- Forging as bodily, sensory labor rooted in Basque tradition

- Iron as “the black light of the Atlantic”

- Public sculpture as ethical practice, not monumentality

- Dialogue with philosophy, especially Heidegger’s concept of place

- Positive and negative space as equal forces

- Gravity and levity explored through balance and suspension

- Light and shadow as materials, especially in alabaster and paper works

- Humanism under authoritarian history, art as cultural survival

Highlight Takeaways

- Chillida sculpts relationships, not forms.

- His abstraction is grounded in place, labor, and politics.

- The exhibition positions Chillida not as a modernist relic, but as an urgent contemporary thinker.

The Forge as Origin Story

Chillida’s biography reads like parable. A goalkeeper turned sculptor; a body trained to anticipate force, to hold space against impact. Jans recalls Eduardo’s return to Hernani, Spain after Paris—adrift, uncertain—until he wandered into a forge and knew immediately what his life would be. He had never worked with metal before. The metal, apparently, had been waiting.

“This is a very physical process,” Jans explains, emphasizing that forging requires not only strength but sensitivity—“touch, smell, sound… all of those things were alive in the process.” For her, forging is not domination but dialogue: “Material itself was so important to Chillida, and he treated it as a co-collaborator in the creation of his work.”

The iron bends not because it is conquered, but because it consents.

Here, Heidegger enters not as citation but as kin. He famously described Chillida as an artist who “lets space be seen.” Jans sharpens this insight, describing Chillida as “not only a sculptor of iron, but a sculptor of space”—one who sought to reveal “the vitality of space, the living quality of space, all of the life of things that are present, but that we often do not perceive.”

Black Light, Atlantic Gravity

One of the exhibition’s quiet revelations is Chillida’s language. He called iron the bearer of “the black light of the Atlantic”—a phrase Jans returns to repeatedly. This is not metaphor but geography translated into ontology. Basque light is not Mediterranean brilliance; it is weight, humidity, pressure. It carries weather within it.

Iron, in Chillida’s hands, becomes a weather system. Pitchforks turn skyward; agricultural tools are unmoored from earth and offered to air. Shadows are not accidents but materials—negative sculptures cast by light itself. As Jans notes, “the shadow is a byproduct of light, but also a material,” fitting seamlessly into Chillida’s vocabulary of presence and absence.

The genius of some sculptures is both the interesting nature of their shape as well as that of their shadow reflections.

Space as Ethics

Chillida’s work is often labeled abstract, but Jans insists—correctly—that it is humanist. His commitment to public sculpture grew from a conviction that art belongs to the commons. Chillida’s own words echo throughout the exhibition: “What belongs to one belongs to almost no one.”

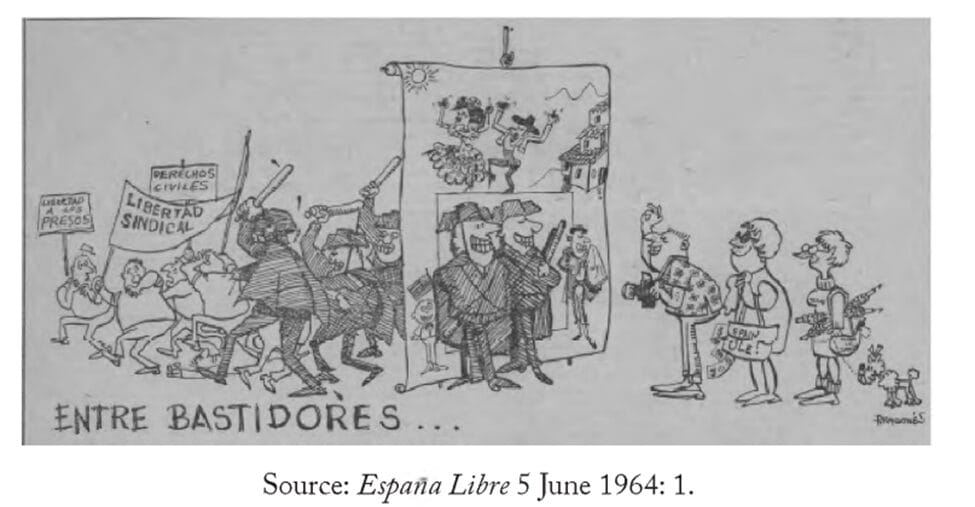

This humanism sharpens against history. Raised under nationalist/fascist Francisco Franco, Chillida lived through the attempted erasure of Basque culture and language. He famously said, “I do not speak Basque, but my work does.” Jans frames this not as loss alone, but as resistance: the sculpture becomes a form of speech when language is suppressed—syntax without alphabet, grammar made of mass and void.

Wood, Architecture, and the Question of Dwelling

The oak works of the 1960s mark a pivot. Jans describes them not as detours but as thresholds. Wood allowed scale; scale allowed architecture; architecture allowed the question Heidegger called dwelling. These beams—once structural supports in Basque buildings—are reassembled using traditional joinery, with no concealment and no tricks.

“They recall Chillida’s direct connection to place,” Jans notes, describing how oak functioned symbolically and materially as a Basque element—“like a tree planted in its terrain, tied to its territory, but with branches open to the world.”

Wood warps. Wood remembers humidity. Several pieces no longer disassemble, rendering travel nearly impossible. Conservation becomes philosophy: how do we care for what insists on living?

Alabaster and Mediterranean Light

After a decade of iron, Chillida turned to alabaster—not to escape gravity but to hollow it. Jans connects these works to his travels through Greece and his early awe at classical sculpture in the Louvre. Here, material is subtracted rather than forged. Light enters, is held, is delayed.

These forms prefigure the unrealized Tindaya Project: a mountain hollowed into a cosmic chamber, open to sun, moon, and sea. Jans describes the proposal as ultimately humanist—an attempt “to rescale the size of humanity,” reminding us that we are only one part of nature, not its master.

These forms are also very reminiscent to the brutalist architecture recently glamourized in the Oscar-winning telling of a Hungarian/Jewish holocaust survivor and Bauhaus-trained architect László Tóth who immigrated to the United States and worked to build grand spaces that resembled the camps and at the same time worked to assist in the processing of trauma in the world. Spending a few moments with Chillida’s works in alabaster gave me a chill and a pause to think of the space within a space, the opening within an inorganic rock that can serve as a place for life and the resonance of all the joys of a life fully lived.

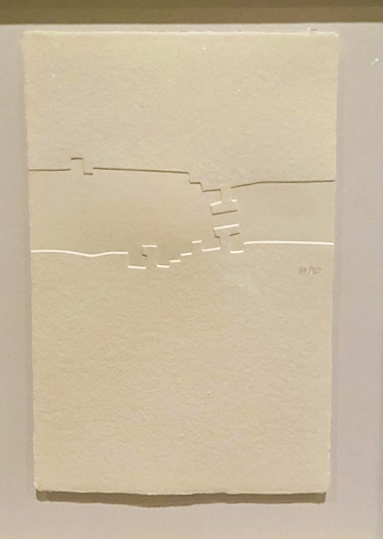

Paper, Gravity, and the Refusal of Glue

One of the exhibition’s quiet triumphs lies in the works on paper. Chillida treated paper not as surface but as body. His Gravitations hang suspended by string alone—no glue, no force. Gravity performs the drawing. Shadows become collaborators.

As Jans explains, these works “welcome space in,” allowing gravity—an invisible but defining force—to complete the composition. Meaning here is not fixed but held in tension.

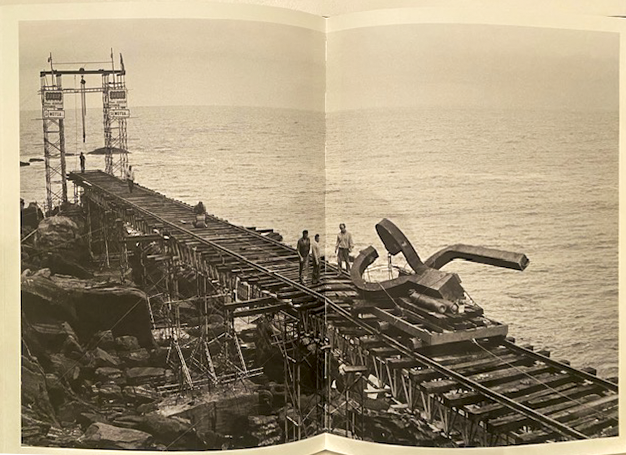

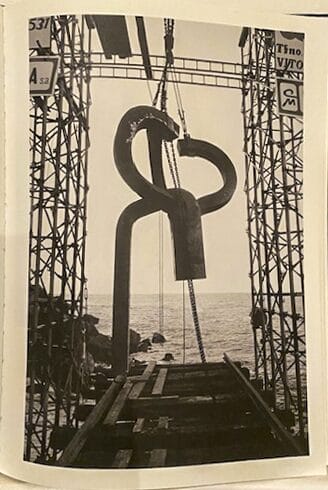

Comb of the Wind: The Work That Breathes

No Chillida exhibition escapes Peine del Viento. Installed in San Sebastián in 1977, the iron forms embedded directly into coastal rock do not resist nature; they invite it. Waves roar through cavities. Wind howls. The sculpture is never finished.

Jans recounted the engineering feat of the construction of this piece of art that lives on the edge of the sea. Placement required the laying of temporary rail track built onto rock in order to deliver the heavy piece of iron set directly onto stone. The beauty of the placement is that there are no anchoring supports required for this piece to live against the sea other than the magic of the big G, gravity itself. All engineer’s know from our physics training that the big G is a constant equal to 6.67430 × 10⁻¹¹ m³⋅kg⁻¹⋅s⁻², first measured by Henry Cavendish in 1798.

F= ( G x (m1 x m2))/r^2

F = Gravitational force

G = Gravitational constant

m1 = mass of object 1

m2 = mass of object 2

r = distance between the centers of mass 1 and mass 2

It is the force that moves planets in solar systems, it is the force that flushes our toilets, and it is the force that scours coastal sea cliffs. Civil engineering meets poetry; permanence meets erosion. It is a sculpture that listens.

I could see a sculpture like this reigning over the San Diego cliffs, perhaps Sunset Cliffs, Tourmaline, or Pipes. It wouldn’t be as kooky as the Cardiff Kook. It would be grand. It would be as Bill and Ted might say: Excellent! Party On Dude!

Coda: What Art Is For

When asked what art is for, Jans refuses abstraction. She frames Chillida’s legacy as an ethic of care: “What if not just artists, but all of humanity treated the world around them with respect?” His work models dignity—how to occupy the world without exhausting it.

It is fitting to turn to Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote:

“Freedom, Sancho, is one of the most precious gifts that heaven has bestowed upon men.”

Chillida’s sculptures do not shout. They wait. They hold. They make room—materially, philosophically, ethically—for freedom to be felt as space, as breath, as gravity resisted just enough to let our light enter.

Eduardo Chillida: Convergence is on view at the San Diego Museum of Art through February 8, 2026. Don’t miss this extraordinary show before it closes. Balboa Park, 1450 El Prado, San Diego, 92102. The museum is open from 10 am to 5pm Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday to Saturday and from noon to 5pm on Sunday.