By Cory Jones

August 22, 2024

Dan recently performed two shows at the JAI at the Conrad in La Jolla on Thursday night August 15, 2024. The concert was part of the La Jolla Music Society’s ongoing Synergy Series. I was able to catch up with him the day after the show for a quick chat about his background, influences, and motivations for continued growth as an artist and a scientist in the jazz music performance space. Below is a dictation of most of our chat.

Cory Jones (CJ) : So, I understand that you grew up in France.

Dan Tepfer (DT) : Yes, I grew up in Paris.

CJ: Which arrondissement?

DT: The 11th. My folks lived in Oregon, and they moved there in 1978. I was born in 1982 and I lived there until college.

CJ: Gotcha. So, Paris – Paris, (not one of those suburbs like the one that Annie Ernaux always writes about.

So, how did you find the European style school system?

DT: It was good for me, you know, I think compared to the American system, it’s quite a bit more advanced at the high school level. Americans have to catch up in college.

CJ: I have a friend from Morocco and he went to school in Belgium and I was imagining that it may be similar to the experiences he had. He was studying textile engineering and he explained that instead of written exams, they individually meet with a professor for a final and have to work out problems on a chalk board and explain the solutions that they work out and that was all very rigorous and nerve-racking.

DT: It’s a pretty strict system.

CJ: Like, strict with a stick, that kind of strict?

DT: Not with a stick, but they will shame you.

CJ: So, shame is used as the educational motivator. Do you think that’s the strong Catholic influence? I have some Catholic friends that talk a lot about the use of shame in their upbringing and difficulties escaping that programming later in life.

DT: Yeah, probably.

CJ: So, you went to school in Edinburgh and then Boston, and now you are situated on the East Coast?

DT: Yeah, I live in New York. I’ve been in Brooklyn since 2006.

CJ: How did you get into jazz and who were your earliest influences?

DT: My grandfather, Chuck Ruff, was a jazz pianist on the west coast. And also through my mom, because she grew up singing jazz standards with my granddad. I was surrounded by jazz and classical music at a really young age. My mom was an opera singer, she sang in the Paris Opera chorus for twenty years. I grew up learning jazz standards from her. So I was kind of “bathing” in jazz from a young age and at the age of six, I started taking piano lessons and just immediately started improvising and it felt very natural to me. I knew it was something you could do, because my grandfather was doing it all the time.

I’d say my earliest heroes were … I got really into Boogy Woogy, like James P. Johnson is someone that I really listened to a lot as a kid and I tried to emulate him. And I got into Thelonius Monk, actually really young, Bill Evans, Keith Jerrett. Ahmad Jamal was a really big one for me too.

CJ: OK, so I’m a little later coming into jazz appreciation. I listened mostly to pop early on, I got into rock in my teens which lead me back to the blues and R&B. I also listened to a lot of hip hop. And a lot of my favorite hip hop artists incorporated jazz into their songs when I was younger (I was thinking of A Tribe Called Quest’s song Jazz (We’ve got), Digable Planets’ Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat), Herbie Hancock’s Rockit, and Gang Starr’s Jazz Thing, where he paired with Branford Marsalis for Spike Lee’s movie Mo’ Better Blues), now I listen to a lot of afrobeats also. I like the interesting and fast paced beats and rhythms paired with a large horn section and a large group of percussionists and dancers. I was a percussionist as a kid, so that always attracts my attention.

DT: I seem to detect that you may not know who Ahmad Jamal is, so he’s [likely] the most sampled jazz musician in hip hop. If you look up “Ahmad Jamal hip hop samples” or whatever, you’ll find out quite a bit about it.

In fact, my favorite album of his is called The Awakening and it’s probably the album that has been sampled the most.

CJ: Do you consider yourself more of a pianist or a percussionist?

DT: Pianist. But, I studied percussion in Cuba. Percussion is very important, but piano is its own beast.

CJ: OK, there were some elements of your concert that were very rhythmically driven and so that kinda led me to ask that last question.

How would you describe your creative process when you’re composing?

DT: [pauses for a sec with mouth full from the yogurt parfait from the coffee shop] It actually changes a lot depending on what I’m doing. I think you have to distinguish between work that is super labor-intensive and work that’s much less so. For example, writing a jazz composition is like writing an outline rather than actual music – there will be 100 or 1,000 more notes in the actual performed music than there are notated on the page. We use short-hand, the way harmony progresses. It’s kind-of like writing a poem, you know? When you write a poem, there are very few words, but they can be very powerful and they can suggest a lot.

CJ: A lot of layers, right.

DT: Well, and they’re meant to evoke something in the reader, and the reader has to create their own world in the few words in the poem. This year, I have three big commissions for classical forces. I wrote a piece for choir and piano using words that my mom left after her death, and a piece for the great jazz singer Cécile McLorin Salvant, who’s actually been here [to La Jolla], and I have a commission for the Eugene Symphony. That’s a completely different endeavor because it’s so much labor, there are so many more notes to write out, so it is much more like writing a novel.

CJ: Right, when you are writing for a symphony, there are so many different instruments to write the music for.

DT: Right, but also nobody is improvising. And you have to write every single thing out.

So, if you’re a poet, you can wake up one morning and be inspired and write a poem down.

If you’re a novelist, you can’t wake up and write a whole novel. It’s just a hell of a lot of labor.

So, it’s just two different ways of making music.

CJ: How do you feel about collaboration in your music? Do you prefer to collaborate or prefer to work as a soloist?

DT: Well, I do tend to err on the side of solo. I seems to be quite natural to me. I’m an only child, so maybe that has something to do with it. I’ve done a lot of solo projects. I think my most successful are solo, but I really enjoy collaborating with other people. It is something that is essential to me. I’ve done a lot of duos. I played for twelve years with Lee Konitz, he’s a [world renowned] alto saxophonist. I’ve done a record with Ben Wendel. And I’ve done one with the McArthur Award winner Miguel Zenon. So duos are really dear to my heart. Also, I have done a lot of trios. You know, piano trios are a pretty iconic lineup in jazz, piano bass, and drums. I’m going to do another one of those real soon. But to work with a larger orchestra is really wonderful and collaboration is essential.

CJ: What has been the most memorable performance you have been to?

DT: As an audience member?

CJ: Yes.

DT: Ah, the most memorable show I’ve been to as an audience member. I have to put hearing the Wayne Shorter Quartet up at the top of the list. That was really magical. I’m friends with Jacob Collier, and some of his shows have been really mind-blowing. They’ve made me re-think what a performance of music can look like.

Wayne is one of the all-time great mystical masters of jazz.

Jacob is an exciting young artist.

CJ: Was it the energy or perhaps more the technician-ship of these musicians that inspired you?

DT: I think for me the best shows have to be both. It’s not really an either/or. … I would add to that list some really great classical shows that I’ve seen, like, András Schiff at Carnegie Hall. That’s just what bubbles into my mind.

I always feel so fortunate when I go to a show and I’m inspired.

CJ: How do you prepare for a performance?

DT: It depends on what the program is. For Natural Machines, there’s a lot of improvisation, and the preparation is really, for me, it’s just really going back into the code and just trying to move it forward. I stayed up all night a few nights ago and just was adding features and tweaking little things. I keep trying to make it better and better. Every time I come back to it, there’s just a long list of things that I wanted to do.

CJ: I noticed when you were playing, as I call it, the ‘call-and-response” section of the programming, your code picks different time periods to “listen” to what you are playing before it gives you a “response” feedback. And it felt like you were constantly changing the time steps that the code responded to and you modulated the proportions of the rhythm in different sections. I was fascinated with that and thought it was really cool.

DT: That’s a great observation, so if you think about canon, just the mere notion of repeating a first voice a little later – implies rhythm. With a composer like Bach, the canon usually stays with one amount of delay – delay is rhythm – a repeating delay. So, with the Goldberg Variations, each one has a set amount of delay and that stays with the piece throughout the variation. But one of the things I got really interested in was metric modulation of the delay. For instance, if you have a delay that’s x amount of time, then multiplying it by three halves or multiplying it by two thirds, you get these really interesting metric modulations that you have to deal with in music. You have to prepare for them in a certain way so that they don’t actually feel random.

CJ: Do you find yourself gravitating to particular fractions? If you think of like in nature, most flowers have five petals.

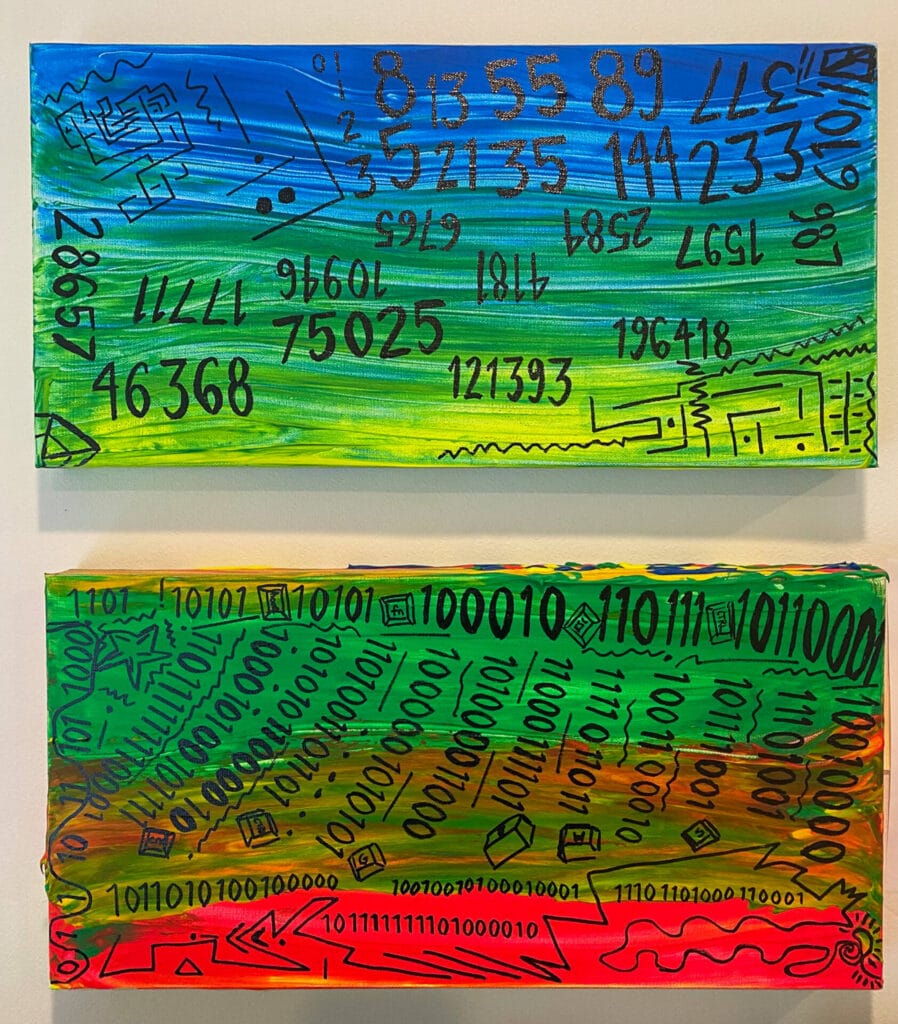

DT: Is that true? It’s interesting because the Fibonacci series shows up in patterns of sunflower seeds.

CJ: [I made a diptych about this series that sits above my work computers in my office.]

CJ: In your show, you also mentioned fractals. Do you have a favorite fractal?

DT: I usually don’t play favorites. In my show, I used the tree fractal in Natural Machines. If you look at it from above, it actually looks like a Sierpiński triangle. So, once you start thinking about self-similarity, there are a lot of connections between different fractals. Anyway, they’re not isolated examples, what underlies them is this idea of self-similarity and they are all members of that same family.

CJ: How much do you rely on AI in your coding now?

DT: At this point, not at all. It’s something that I want to explore, but I’m less interested than you might think. What interests me is not actually replacing the human, but augmenting the human and AI mimics humans, it learns from humans. But I’m more interested in teaching the computer explicit rules because then it’s exactly [what I want.] The problem with AI is it’s a black box, right. I prefer to know exactly what the computer is doing because that’s what composers do.

CJ: In your concert, you mentioned the term “degrees of freedom.” To an engineer, like myself, I associate that term with the mechanics branch of physics; a rigid body has six degrees of freedom, three translations and three rotations (, or like Euler’s angles.) But you used it in a different way, so remind me.

DT: Yeah, so pretty much all music that stands the test of time has certain things governed by rules. Some music has more things governed by rules than others. For example, the movement of serialism, which began with Arnold Schoenberg back in the early twentieth century, has a system for generating melodic material. Composers that followed him after the Second World War, the so-called total serialists expanded on this and used the serialist system to control not only the melodic pitch pace, but also aspects like rhythm, dynamics, timbre, and form – and basically the whole composition would be formed by a serialist process. And that music has very few degrees of freedom. I would say it is a very “over-determined” piece of music.

Now at the other end, you’ll have somebody who is just beginning to play music and [their playing] might be haphazard, they may not understand “the rules” – and that [music] would have too many degrees of freedom.

The genius of Bach is that the rules are extremely powerful and they help to structure the composition, but they are not too powerful and they leave a lot of things that are not determined by the rules. You then have to bring something into it – like emotion, intuition, and spirituality.

So, the notion of degrees of freedom is just short-hand for distinguishing between what is fixed and controlled by laws and what is free.

CJ: So, do you mean how is your free-will implemented into the song?

DT: So, the debate about free-will is that obviously there is no such thing because – there is a great Schopenhauer quote that says something like

“A man can very well do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wants.”

It’s such a critical idea. Like, you can do what you feel like doing, but you can’t decide what you feel like doing. When we’re talking about intuition, emotion, and spirituality in music – who knows where it’s coming from – it might not be your decision.

Often, it feels like you’re channeling something, right? But it still counts.

CJ: Yeah, it is like, just a feeling, when you get into a groove.

DT: Exactly, and the point is that a portion of the music is controlled by laws and a portion of the music is something much more mysterious. The laws are completely known, you just have to understand them very well and you leave room for mystery.

CJ: So, do you find yourself particularly spiritual or do you practice a particular religion?

DT: I grew up Jewish, but I don’t … I’ve always felt very spiritual, but in my own personal way. For me, it manifests in the fact that I feel that the world around me is very inhabited. And if I go deep inside in a meditative space there is a whole world there. There’s a lot of room for mystery for me even though I’m like a total scientist.

CJ: When you are in your groove, do you feel like you’re in some sort of bardo state or do you feel like is there some other spirit inhabiting this sound that I’m getting?

DT: Yeah, for sure there’s something else going on when it’s really clicking and working – basically your ego goes away. That’s the best thing about making music to me. It’s a spiritual practice that allows you to transcend the ego. In the best case, it’s like you’re catching a wave that’s not your wave. Your job is just to stay on the wave. It’s not something you’re making, it’s something you’re riding. I feel very lucky to get to do it.

CJ: So, waves and surfing – are you a surfer too?

DT: I’m a pretty serious kite-surfer, but while I’m out here I do want to get out and try to do some surfing.

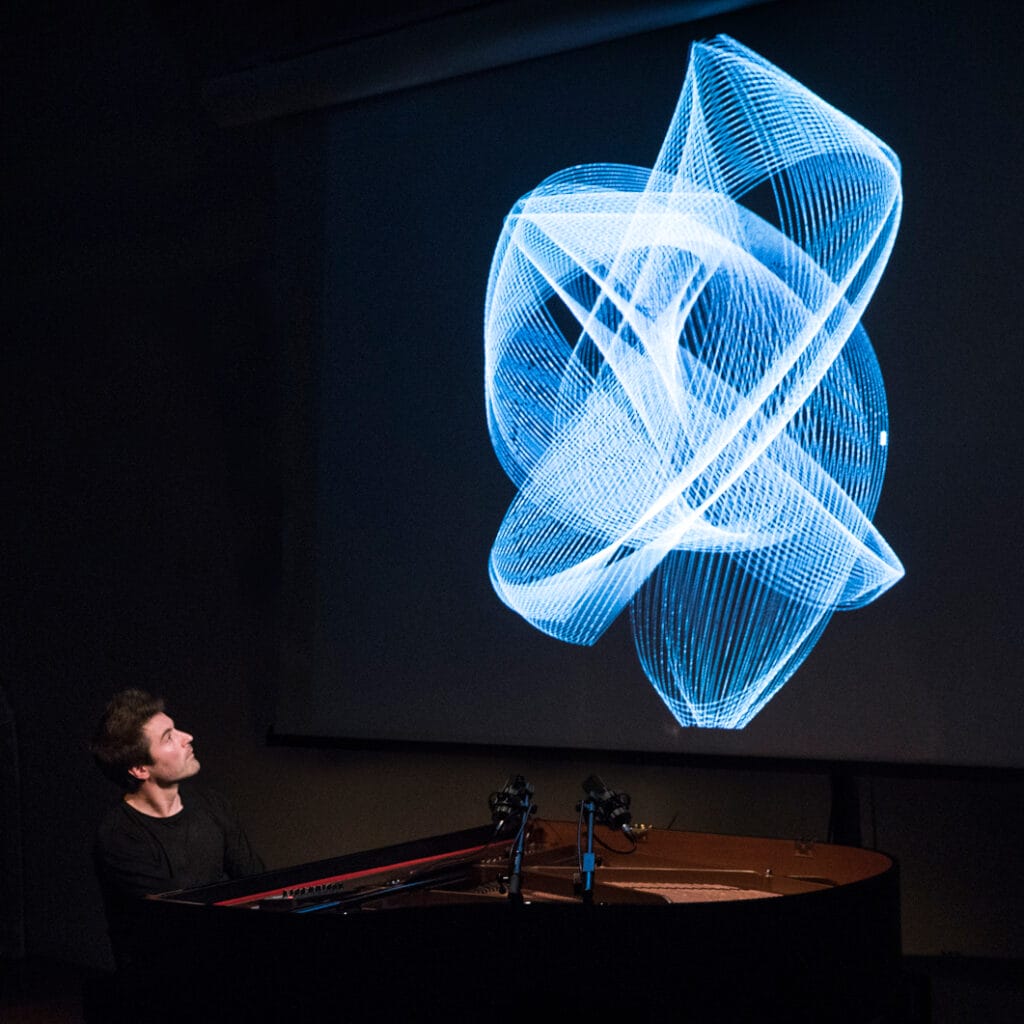

CJ: There is a lot of visual representations of notes in your show. I thought it was really fun how you picked different visualizations of the notes in the various pieces. The different shapes equated to the different timing of the note – how long is it, and you can see without the use of the lines on a music sheet the ascending and descending tones.

When I listened to your “Inversion” song, there was this two beat and a response two beats that repeated with overlaying harmonies and the visualization. And that repeating pattern rhythmically reminded me of a heartbeat – and then your visuals appeared to transmogrify into what reminded me of something you see in a hospital, like an electrocardiogram (or EKG) display. Was this your intent for you were seeking when you were coding the visualization?

DT: No, I wasn’t thinking about it that way, but what I am thinking about with all the visualizations is what is the core element of this algorithm, of this system of rules, and how can I make that as obvious and clear as possible in the graphics? In that one, I tried to pair it down so that the symmetry between the two lines was very obvious.

CJ: So, I know that you are also an astrophysicist…

DT: [Interrupting] Well, I wouldn’t call myself an astrophysicist, I just have an undergraduate degree in astrophysics. It’s been a long time, don’t ask me to do an integration.

CJ: There were many ball-and-stick illustrations in one part of the show. How much chemistry did you study in school and did that perhaps influence your representations there? For me, it reminded me of Organic Chemistry class a lot. (Organic chemistry has a lot to do with living things -it’s the study of carbon chemistry and all living things use carbon as the base element of our biological structures, except for some very small plankton that are silicon based, and one old original Star Trek episode explored the possibility of another planet having conscious beings based on a silicon platform in another permutation of potentialities.)

DT: I did a little chemistry, but not a lot. We didn’t have many chemistry prerequisites for my undergrad. I think one of the things that I love about this project is that the coding in it is pure joy for me. I’ve been doing this kind of creative coding since I was a kid and I just like to mess around and find things that I like. The best things that I found were often from mistakes that I made while coding. It’s a very child-like process. So, I’m never setting out to make it look like anything in particular, I’m just kinda messing around. Maybe there’s something in my subconscious, I’m familiar with those molecular structure sculptures and so maybe that’s an influence. I don’t know.

CJ: What code do you use to write your keyboard programs?

DT: SuperCollider mostly. It’s a pure code environment for music, it’s a real-time coding environment so you can write code and execute it on the fly. It’s really great for iteration. [So, there’s no delays for compiling.]… For the graphics, I use an environment called Unity. Do you do much coding?

CJ: No, I had to learn Fortran in school but I don’t use it much. (Also, a little html, DOS, and Visual Basic).

CJ: The section of your performance where you had a series of vocal responses to input keys was really fun – it reminded me a lot of this show I went to a few months ago back, up in Berkeley, where Bobby McFerren has an acapella group at this small coffee shop with an auditorium called Freight and Salvage. They do a similar sort-of call-and-response where they have the audience participate and start off a song, and then the acapella group then takes that input and riffs off of it to make a whole new song. And they basically go around the room to see if they can get another new song starter to work with. Part of your show with the vocal inflections, it really reminded me of a spontaneous music-making process.

DT: People have asked me to make available a public version of it, I intend to – I haven’t done it yet. It is really fun to play with. The balance between algorithm and mystery is really interesting – in order to make the canon work, you have to use particular intervals, so you have to also be thinking of performing in a very rule-based way.

CJ: Dwarf Star Harmony. I had some cosmology in a geochemistry or mineralogy class and that segment of your show reminded me of the life and death of solar systems – the conservation of mass and energy in the universe. Was this part of what you were thinking about with this portion of the show?

DT: I think the larger idea here is the notion that relationships between frequencies are critical to everything. Planetary orbits and the relationships between the different periods of planetary orbits is just one representation, or one instance of relationships between frequencies. Harmony in music is another instance of that. Since I was a little kid, the infinite-ness of the universe absolutely boggles my mind. There is also a very unifying element to this and that is that the planets are also making their own music.

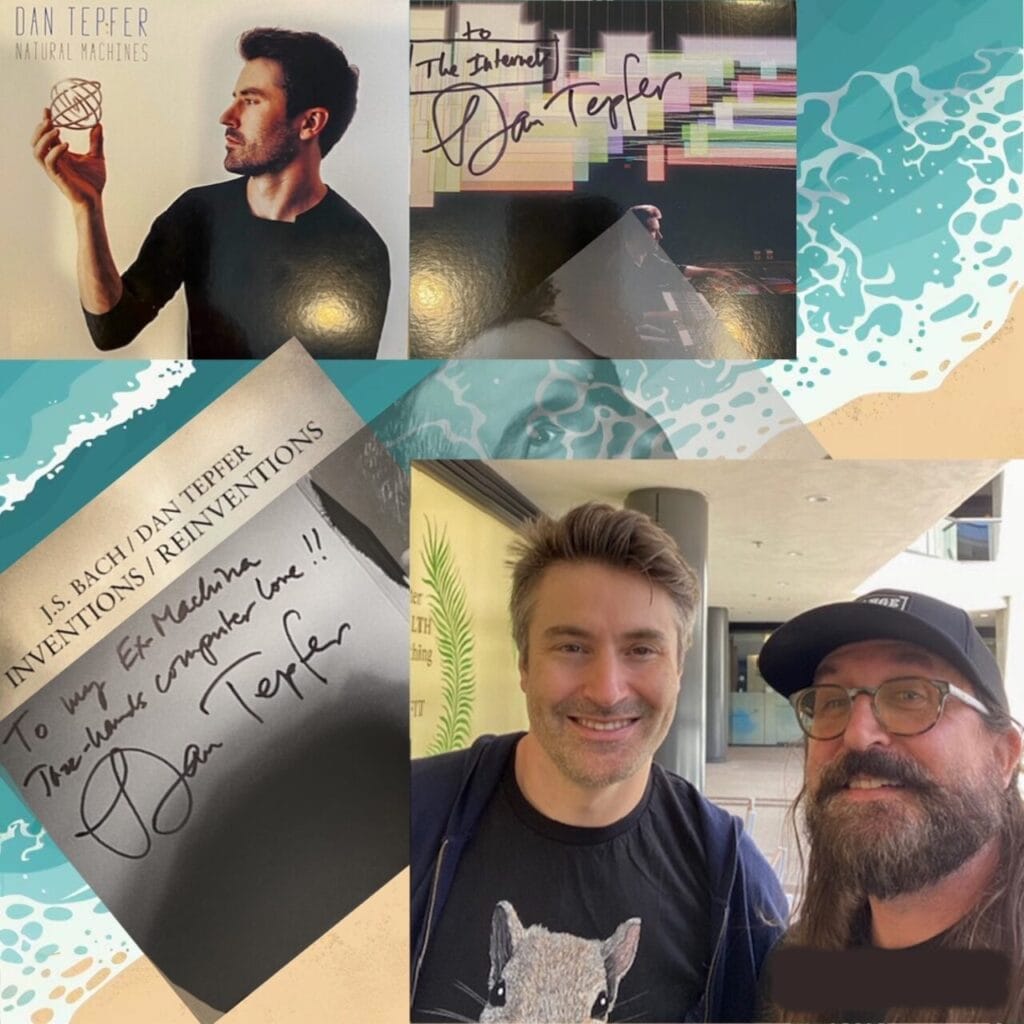

At the end of the show, I picked up a couple CDs, unfortunately he didn’t have any vinyl. He was signing autographs and he asked me who to make them out to, and so I said to make them out to The Internet and to my good friend Ex-Machina Jazz-Hands Computer-Love and he obliged.