By Cory-LaNeave Jones

September 18, 2025

In the hush where thread whispers its secrets, the quilt becomes a poem, each patch a syllable in the story of souls unseen. There, Bisa Butler stands—her hands luminous with memory, her eye attuned to the hum beneath printed cloth. She draws lineage from corners of West Orange remembrance, from Ghanaian Kente and her grandmother’s careful seams. How does a cut piece of fabric recall migration, maleness, mothering, resistance? In her world, scraps carry ancestry and fragments echo ancestors.

“Don’t you know that spirits talk, ‘n they take you places?”

– Henry Dumas, Echo Tree

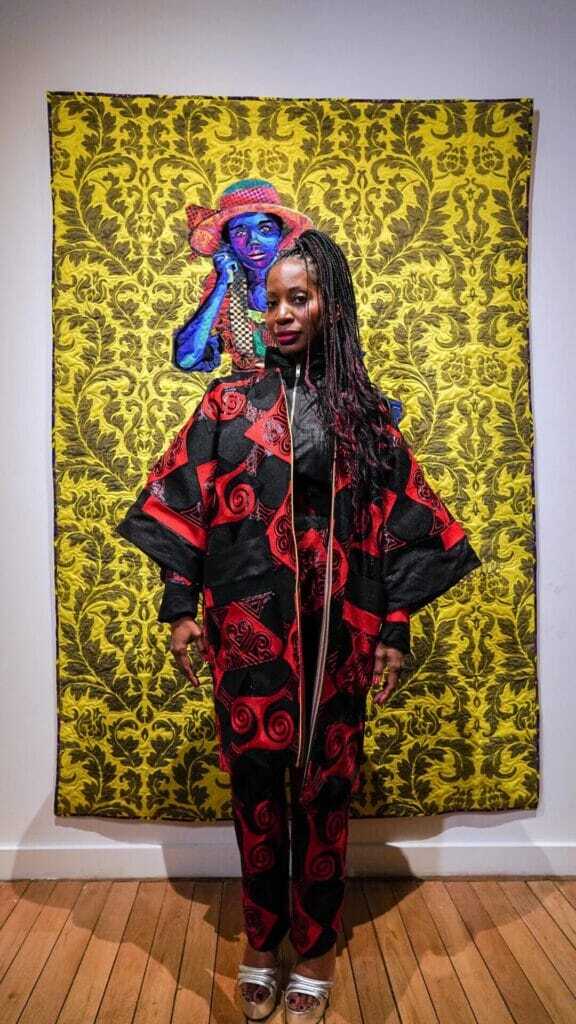

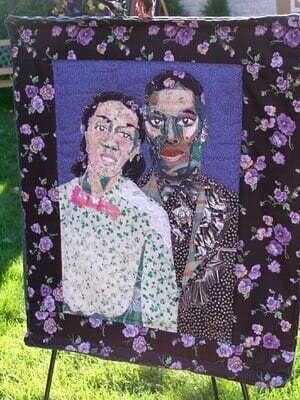

She was Mailissa once, born in New Jersey in 1973, the youngest child in a house shaped by Ghanaian and New Orleans heritage. By age four, she was coloring worlds; at Howard University—a painter in training—she absorbed the collage wisdom of Romare Bearden and the stitch-wisdom of AfriCOBRA. Graduate school brought a turning: nauseated by paint and moved by memory, she pieced the first quilted portrait of her grandparents—Francis and Violette—and everything shifted.

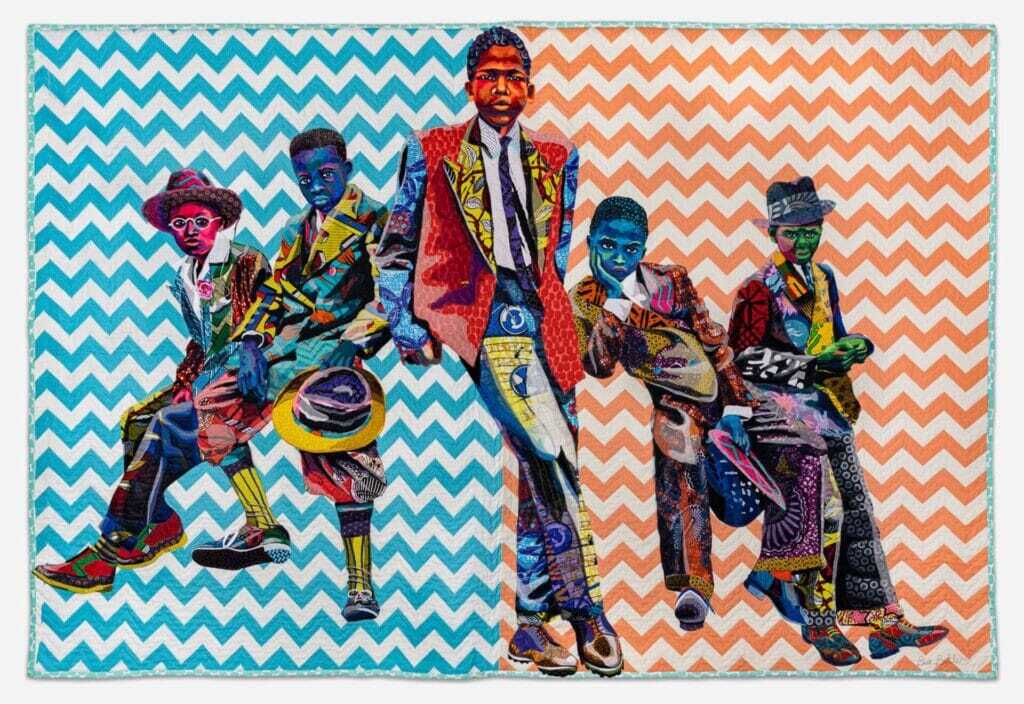

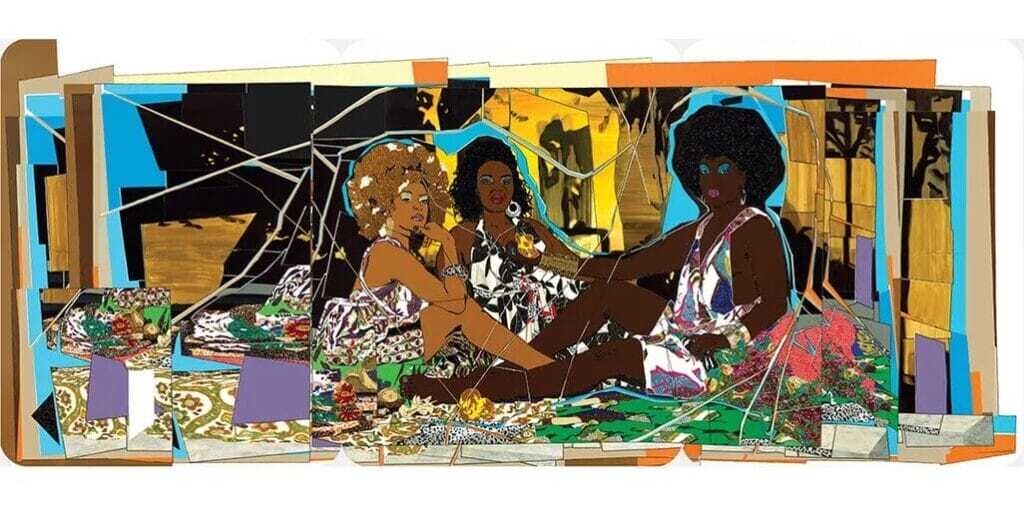

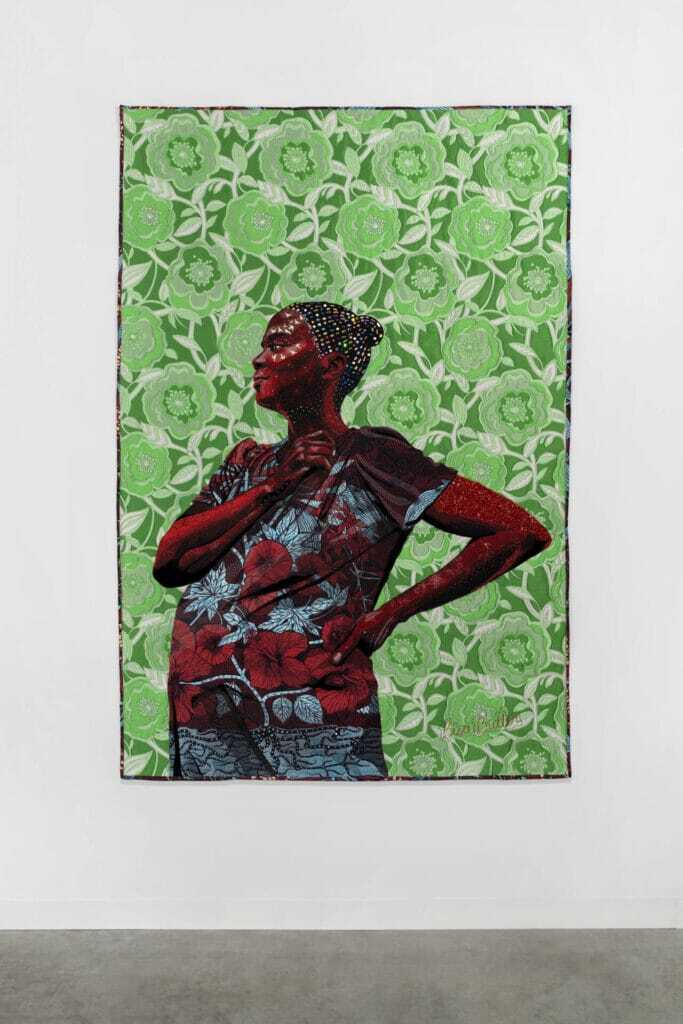

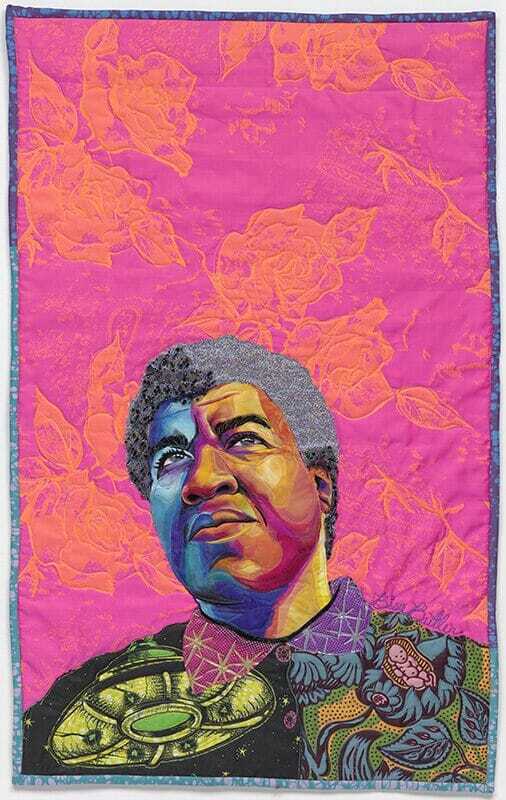

Since then, her quilts—bodied in jewel tones and layer upon layer of nylon, silk, cotton, chiffon, brocade—have transformed craft into canvas, intimacy into monument. Her figures “look the viewer directly in their eyes,” asking to be remembered. She draws from family albums, found photographs, the legacy of quilt-makers like Faith Ringgold, and the vibrant logic of AfriCOBRA.

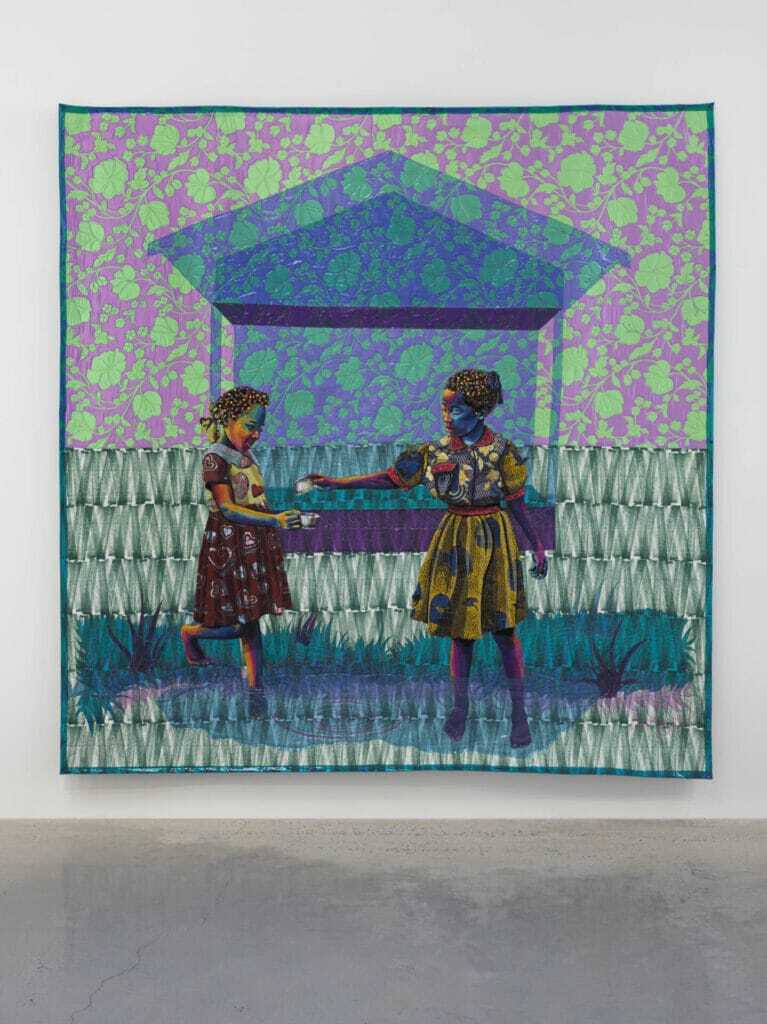

Her first solo museum exhibitions—Portraits at the Katonah Museum of Art (2020) and the Art Institute of Chicago (2021)—unfurled more than twenty life-size portraits across galleries themed in migration, youth, and legacy. Among them, The Safety Patrol stands guard, a boy’s outstretched arms shielding his community, quilted in defense and love.

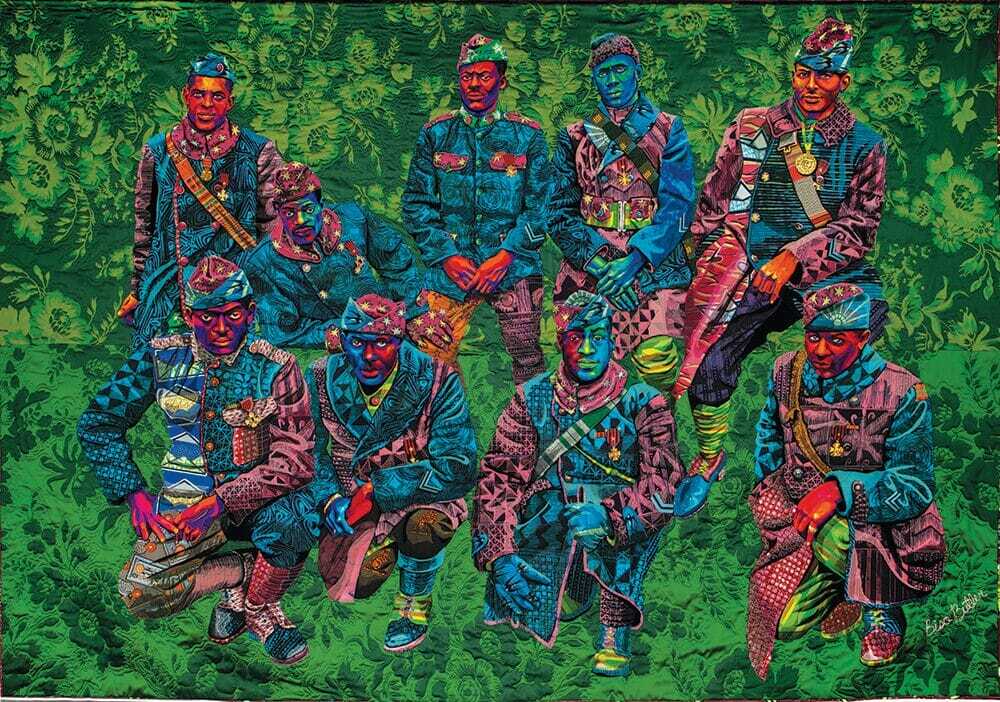

Her monumental Harlem Hellfighters quilt gazes upon Black World War I soldiers whose sacrifice has often been minimized in American memory. The full breadth of their American memory became woven into fabric by Mrs. Butler’s magical hands.

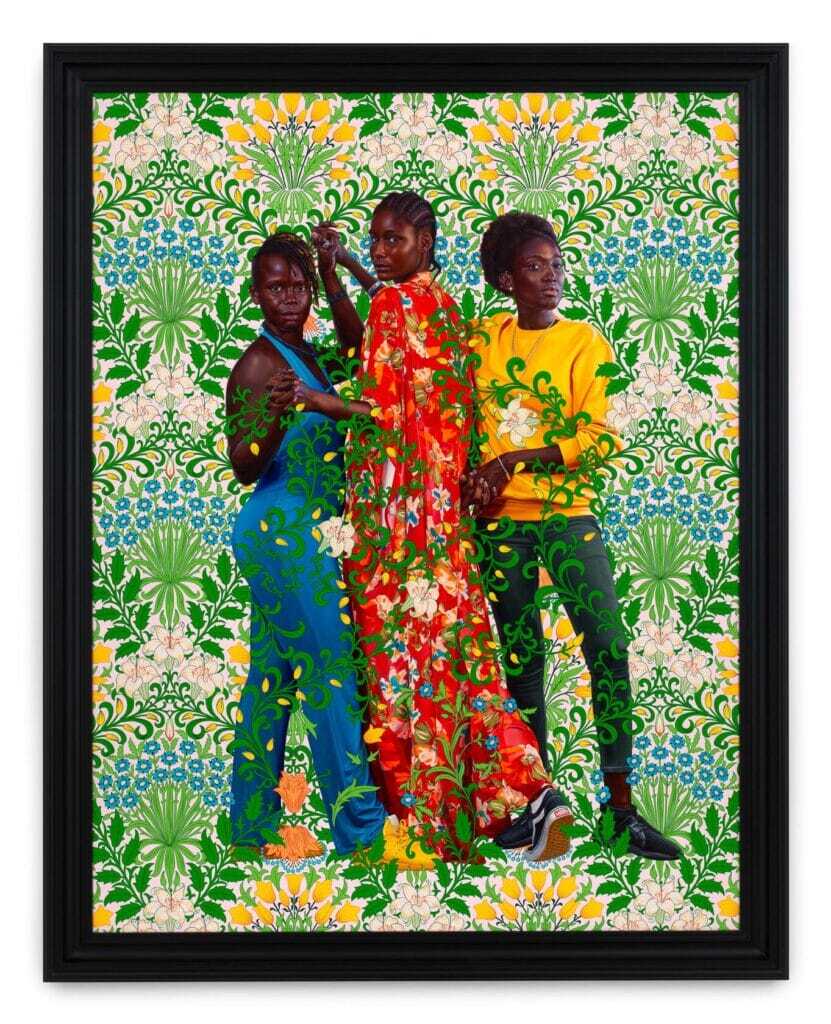

Butler’s art has also adorned the covers of Time (“Guardians of the Year” 2020, “100 Women of the Year” 2020, Time Magazine), Essence (Essence Magazine), and Juxtapoz (Juxtapoz Magazine). Each of these portrait insist on visibility, reasserting Black life in vivid color. Kehinde Wiley takes portraits out of the frame, she notes, but her method translocates intimacy itself into kaleidoscopic monumentality.

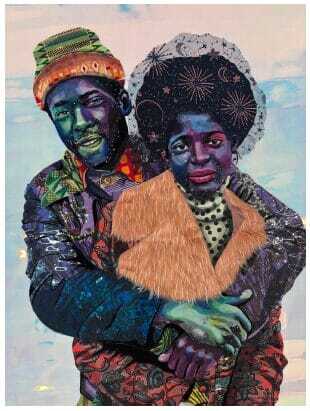

Her new work is focused on healing our emotional state by focusing on the warm embrace that we all need when facing difficult times. I was able to chat with her via zoom the other week to discuss her new work.

Opening: The Grounding — On Choosing a Subject

When you choose a subject, do you see them first in fabric, or in flesh?

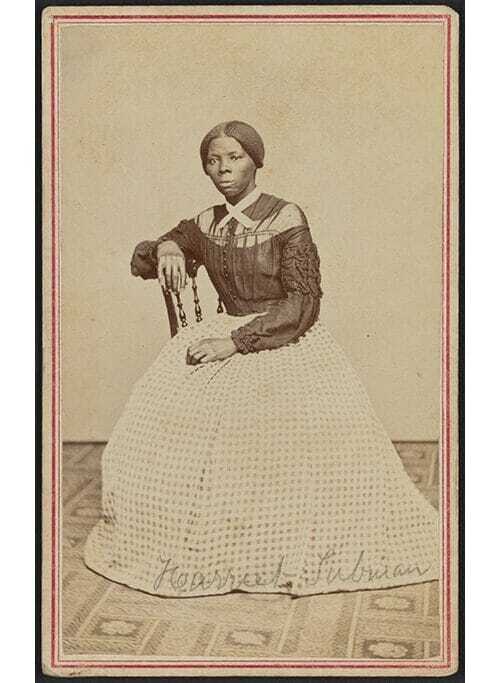

Bisa: When I choose a subject, I’m mostly looking at black and white photographs, definitely (I see them) in the flesh, but there is a separation between the world and somebody else’s view. I have the privilege of existing in a time where photographs are available and the photographer’s brilliance, their original vision of what they were looking at, is what draws me in (to) their composition – their subject choice. I always talk to photographers because they have to capture everything in less than a second. It takes me months and months to get my vision together.

And it’s also cool to have access to a photograph because now you have the vision of the photographer who photographed Harriet Tubman in her forties, and not only are we seeing what Harriet Tubman looked like, but you’re also getting the insight into this other person’s mind, what they thought about what was important. Then I get to interpret that, think about them, and their subject, and then I get to interpret that for myself and fabric.

Fabric as Memory

Your portraits transform cloth into something almost breathing.

Do you think fabric carries its own memory, separate from the sitter?

Bisa: Absolutely. I think that’s what makes my work so accessible because everybody, I (think) everybody looking at it understands fabric as they stand before the pieces, or (are) scrolling on a phone, like you’re wearing fabric. If you’re not wearing fabric, you’re sitting on fabric. You’re literally in physical contact with my materials from the moment you’re born and the moment you pass away.

If they see denim or leather or sequins, they know how that fabric is worn and what I might be trying to say about a particular person. And then if the fabric is worn already, if it’s vintage, that also carries a resonance of whatever the original purpose was.

Those people were West Africans who worked with indigo dye.

Denim, she reminds us, began as a cloth of enslaved laborers. By the 1960s, activists wore denim and overalls as reclamation: “It’s not something to be ashamed of because you work as a sharecropper. My grandparents were enslaved people and I’m proud of them.”

I started using vinyl and anybody who was alive in the eighties, knows it’s the fabric (used in) the jelly clothes. It brings you back to a specific memory, which is because that gives my artwork this resonance that I don’t have to create. The viewer is looking at it and they’re attaching their own memories to that cloth, and it makes it so much richer.

On Influence and Dialogue

Asked about her artistic resonances, Bisa Butler places herself in conversation with peers and ancestors. She nods to Mickalene Thomas, Calida Rawles, Barkley Hendricks, Faith Ringgold, Kerry James Marshall. “I go to these shows and absorb what they’re doing… What can I extract that I can say in my own way?” Her quilts become visual remixes, much like her husband John Butler’s DJ sets layering James Brown’s syncopation over hip hop tracks.

Color as Voice

Can fabric shout? Whisper? How do you translate tone into thread?

Definitely. It’s funny the way Black people dress and the way they call out things. I remember in the eighties, and I think it was an older phrase, but my stepmom would say, if an outfit didn’t go together, they would say it was “loud” and it was “tacky.”

Loud was bad. And I noticed that all the NBA (National Basketball Association) teams, they always use these contrasting colors. They’ll put the Lakers with their yellow and purple, and those two colors are opposite each other on the color wheel, and because they fight against each other, they are “loud” when you put them (on). And so I do that on purpose. I use a lot of contrast and I’ve heard some criticism. Some people just don’t dig it. They think it’s just “too loud.” I’ve heard people say “her work – some pieces are just too bright.” I love neons. I grew up in the eighties, so I remember we used to call it fluorescent. That was brand new, and that was it. Like, You were it, if you came to school with a fluorescent shirt on.

I’m a descendant of folks who were saying it loud, they were black and proud in the sixties, so I was born in ’73. My entire childhood – All of my Aunts, mostly all the time would be wearing some sort of African print fabric. These were my American Aunties that was really popular, and they all had the Afros, so I love that fabric.

In my little toddlerhood pictures, I’m wearing a little tiny miniature dashiki, so I’ve worn that fabric. I’ve seen that fabric and one brilliant thing, about the African textile artists and creators, they really have been using contrasting colors for years.

Whatever their techniques are, they’re able to put a yellow dye next to a purple dye and not have them bleed together and become a strange shade of brown or gray – using their wax resist, or however they’re doing it. They’re able to do colors that traditionally you can’t put next to each other in a wet surface, and they love them. They wear a lot of contrasting colors, which is very different than the traditional American pattern makers and designers where the fabric you wanted, colors that go together – they don’t “fight.”

And so they whisper.

That is something that an artist can control, and I have tried to control that. I have a new piece where I use mainly shades of blue and black, but I used a lot of different textures of blue and black, blue lace, blue netting, blue tulle, blue rhinestones, blue sequins to give a subtlety that would not be there if I had used blue and yellow, or blue and orange colors, that blue might fight with more and then suddenly it would be “louder.”

I think about color as a way to create a mood. If I’m trying to create a portrait of somebody who I think might’ve been more cool, more soft spoken, and maybe more introverted, I’m going to use colors that don’t fight. But then if I want somebody to appear very strong and bold, I’m going to just go for it. It’s going to be all of the neons and varying textures, and none of the colors are going to go together. They’re going to war with each other.

Sound as Structure

What is the first fabric you ever cut, and do you remember its sound under the scissors?

Yes, I remember because my mom had her sewing room (in the) peak ‘70’s, and she was always replicating designer clothing. Halston was big at the time, and she didn’t have Halston money, …

Cory: Not many people do.

Bisa: Right?!

There used to be Vogue patterns, so you could get the Vogue magazine, and then in the magazine there’d be a model styled – and at the bottom of the page it would say the Vogue pattern number, and then you could go to the fabric store and she would get that pattern. Not that Vogue was knocking off Halston, but it’d be like “Halston-esque.”

And I wanted her, so I’d be playing on the floor at her feet. I was a very small child, and I knew better not to touch the sewing table because there were always pins, needles, sharp scissors. I asked her, I was constantly asking her to stop what she was doing and make clothes for my Barbies. Then I remember, one day she was like, okay, No. – I wanted pants for Ken, and Ken only had, I guess his one little, he had shorts or something. It was like Malibu camp. And my mother, she took the fabric out, she was working on tweeds. She must’ve been making a tweed suit, which the construction of that for me is so beyond what I want to do – and she gave me some of that wool tweed and showed me how to pin it together and how to cut it out – and I do recall the sound of her scissors. She had those heavy metal shears – cutting the wool – which was kind of thick – and I made the most awkward looking pants for Ken – there was no elasticity, it just went straight up, like stove pipe style. That was the first thing I ever sewed. It was a pair of pants for Ken.

Cory: You gave Ken a pair of Coco Chanel styled tweed pant-suit pants – That’s cool.

Music permeates her practice. “I want my artwork to be able to transform what you can’t grab onto.” She compares her process to composition: piecing fabrics is rhythm, layering color is harmony.

The Gaze of Fabric — Memory, Lineage, Legacy

Roland Barthes wrote of the “punctum” in photography—the point that wounds you. Where is the “punctum” in a quilt?

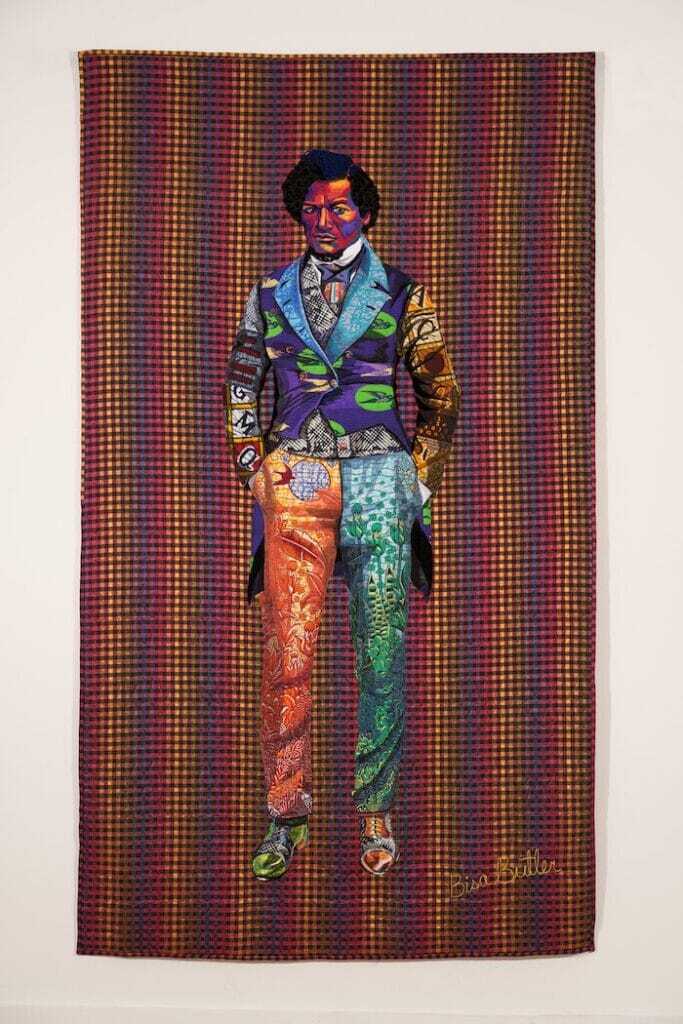

I think that the point that connects me to that image and then connects anybody looking at my artwork to an image that might hit them at their most vulnerable point is the eyes. And if I can’t capture that gaze, I think it’s between the eyes and the hands that really seems to touch people.

If I can capture the gaze, then I’m good. It doesn’t have to be exact, but there are some people whose gazes are so electric that it’ll go through time and space, even just a glance of it. I feel like Frederick Douglas is one of those people, known as the most photographed man of his century. It was so important to him to put everything he had into the gaze because it was his carte de visite, it was the calling card, not just for himself, but it was for all black people.

He would say that Black people are human beings and are intelligent, so every image had to look a certain way. I have read that he was very particular. I think one photographer captured him smiling, and he made the photographer not use that image.

Because he wasn’t looking for a docile image. It was an afront, a provocation, and so when I tried to create his portrait, I got so much more than I realized I was going to get. He was very good looking when he was younger, so I was thinking, I’m just going to capture young Frederick Douglas, but it did touch me deeply.

I could see a big bloodshot, a damaged blood vessel in his eye. I was simultaneously reading his autobiography, and he had said that he almost lost his eye over a beating. To see that the damage was still there, it was just something that it did to me. To be able to capture that, I do think that it felt like that was it right there.

I had zeroed in on his literal wound, and by me capturing it, I was sharing it with everyone else now, I felt like it was a through line, a window to connect us to this man and then connect us all to our humanity that we as human beings, we can feel pain and we can suffer.

Storytelling Across Mediums

You’ve said quilting is storytelling—what happens when a story resists you?

I don’t. The blessing about what I choose is that I’m drawn to photos that speak to me in the first place. So I have worked with images where I just can’t see it well, especially if they’re really old and they’re not a good resolution. If I can’t see what’s happening in the photo, then I would say the story does resist me.

Some of it is lost through time and I can recreate it. I was working on a portrait of the Harlem Hellfighters who were a World War I unit, a segregated unit, and some of the soldiers’ faces in the photo were a little grainy, but my husband was helping me with that, and he was saying, this guy, he looks like, an 80’s rapper, Lovebug Starski (a.k.a. Kevin Smith).

According to an article published in the Observer on June 15, 1986 “Kevin Smith (a.k.a. “Lovebug Starski”) was the guy who “picked up the mic and just started saying ‘a hip hop, hip hop, de hibbyhibbyhibbyhibby hop’. The people couldn’t believe it but it stuck.”

a.k.a. This is the guy who coined the musical art form term “hip hop.”

He was like: “This guy looks like Lovebug Starski!” And he went and got, my husband’s a DJ (Disk Jockey), so he has all the vinyl with the record album cover art. So he went downstairs, got the record, brought it up.

So I’m looking at this photo of Lovebug Starski, and I’m looking at this photo of this young 19-year-old soldier taken in 1919, and they did have similar features. And then, so looking at the photo of Starski, then I got it. I was like, “Okay!” I can’t capture this young man’s photo completely because I can’t see it, but I have somebody here who very much looks like him. I don’t know if he’s any known descendant, probably not, but sometimes if I find that the story is what I’m trying to read, you know “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I have to go to someone else’s story (or) somebody else’s image that can help me understand what I’m saying.

On Resistance and Legacy

Do you feel you’re in conversation with painters, photographers, or griots? Or all of them at once?

Story tellers, Definitely, all (of them). I think I’m surrounded by so much information. We’re just trying to understand the world and my quilts are my version of that. So you get to see visually how I’m interpreting the world. It can be something that I heard, it can be a myth or a story, it could be a poem, music, a show that I went to that day.

I have two daughters who are in their twenties, so things that they’ve told me and music, very much so from my husband’s influence, and music that’s around me. He’s a hip hop DJ, so as you know (with) hip hop, they’re always remixing things that are old.

He plays a lot of James Brown and James Brown was brilliant. I mean, I could probably spend the rest of my career just trying to get into the compositional dexterity of James Brown and all of his influences. It’s as if all of the influences that James Brown had from the church and the south and the sixties and rock and roll and all of those things. They’re in his music, but as I’m in the studio listening to it now, they’re also affecting what I’m doing. So I get to have a little bit of these things in there. I think of my work more similar to what a DJ would does because I’m so attracted to things that are old and reinterpreting them again. So, it’s like I’m remixing these photographs.

Harriet Tubman existed in this 3D (three dimensional) world of color, but we’re not there. We just have this machine, the camera’s version of her. I’m trying to connect with the Harriet Tubman, not just the (black & white, or sepia) photo of Harriet Tubman, and I think that’s what my struggle is. (It’s) me trying to understand her, the actual woman. How do I capture some of that?

Especially in moments like these, when you have to be brave, and you have to be strong.

I think about her a lot and how my version of bravery – it’s like one minuscule – it’s not even an eighth – I don’t even know how much bravery I would have to need to be like her.

…

Quilting, Butler reminds us, is survival and signal, warmth and rebellion. “I feel like when I quilt, it connects me to women, African-American women who came to this country and needed to keep their families warm… but also to women in my ancestral line from northern Ghana.” The quilt surface becomes an archive, stretching back to prehistoric cave handprints, tying Butler’s stitches to the deepest threads of womanhood.

The Burden of Black Genius

I recently watched Questlove’s documentary on Hulu, “Sly Lives!” about Sly Stone, and so he asked the following question to everybody he was talking to at the end, so I wanted to ask it to you.

What do you feel is the burden of black genius?

The burden of Black genius, I feel was the burden and the responsibility was passed on to me. When I first got to Howard University, I was just 18-year-old kid from New Jersey. I just wanted to go to Howard because I thought the boys were cute. I didn’t have a real concept of an HBCU. What did that mean? What was it for?

It was more (than) a university. It was to help black people assimilate into the wider culture as the white culture, how to not “pass” in a way, but become somebody who’s really interested in slow progression and fitting in, rather than saying, I’m a Black American, and that’s something different, and I’m proud of that.

Howard’s motto is (Veritas et Utilitas, or) “truth and service,” and you knew it and you lifted it, that you’re here because somebody sacrificed for you.

“Not only are you privileged to be here, but you have a responsibility… This baton was being passed down directly.”

Professors who had lived through the Black Power era instilled in students the idea that art was not a private luxury but a public trust. She recalls the legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois’ “Talented Tenth,” which framed education as an obligation to serve.

Museums and Community

Asked which museums she returns to most often, Butler points to the Brooklyn Museum, her daughter studied at Pratt (also in Brooklyn), and to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which welcomed her students during her 15 years of teaching. “I’m drawn to museums that open their doors for ordinary people and for people like me, a mom with little kids, who need culture.”

Books, Music, and Imagination

A fan of science fiction, Butler credits Octavia Butler as a guiding presence. “I’ve been obsessed with Octavia Butler since the nineties.” She recalls how Parable of the Talents eerily forecasted political slogans that would reappear decades later. For Butler, Afrofuturism is both a mirror and a map. She also has been reading the Diana Gabaldon, the Outlander series.

Soundtrack of the Studio

Her husband John Butler, a well-known DJ, curates the music of her studio. Clyde Stubblefield’s “Funky Drummer” loops through the speakers, reminding her of hip hop’s sampled foundations. “That man, his rhythms basically created hip hop.” The quilt, in this context, becomes another remix—fabric instead of vinyl, stitches instead of beats. “I’ve been listening to a lot is Kool & the Gang, who, they’re the most sampled group for hip hop.”

She said that her husband also plays original tracks followed by sampled versions, and this reminds me of the “scramble mix,” produced by a DJ named Scram Jones, where he plays a mix on the weekends doing the same process. It comes on Eminem’s station, “Shade 45.”

On Influence and Admiration

Which artists, historical and contemporary, do you most admire the most?

The most? I would still have to say hands down Faith Ringgold, but I have a whole list. I would say that the artists who influenced me for this show, Karry James Marshall and Elizabeth Catlett. I saw her show recently in Brooklyn, just blew my mind away. Jack Whitten, his brilliance, his note-taking blows my mind away. And Lois Mailou Jones and Alma Thomas. I’m always looking at black women artists, in particular, because I admire not just the fact that they were successful, but Elizabeth Catlett in her activism. She married a Mexican artist and she was caught up in that red scare – accused of communism.

I think she lived outside the United States for the rest of her life, but she did come back to the US as an elderly woman, and she received awards for her work. Even James Baldwin, though he wasn’t visual artist, but these are the artists who really influenced me on how to move forward, not just in what you’re creating, but what you’re saying. – What are you standing for and how are you living.

I love to see them, James Baldwin looking fly walking down the street in Paris, or smoking a cigarette. I love to see people thrive, and that’s what I want. I don’t want a starving artist experience.

Final Question:

What is Art For?

What is art for? I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately. I think art, what is it for? It’s to help us think, and help give us hope, because with art, you can create any world that you want.

You can think of Octavia Butler and imagine the world a thousand years from now—when you get a vision, you can create a song that people can listen to for a thousand years and it can transform them into a place of peace or tranquility, or it can drive up their heartbeat and make them want to tear something apart.

But art can move you and can be a vehicle to remove you from your physical being and take you somewhere else. And I think that we need that. We need to have the escape from our physical constraints. You see a lot of art from people who are incarcerated who make beautiful art. And we have seen throughout the world some of Van Gogh’s most beautiful paintings created while he was institutionalized. He needed that. And we also benefit from the visions that people create.

Closing: Holding Close

Toni Morrison wrote in The Nation (“No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear,” March 23, 2015):

“This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge—even wisdom. Like art.”

These new works in her exhibit titled “Hold Me Close” support her feelings that we need each other more than ever in times of crisis. She feels we all need more humanity and empathy. She reflects on the old Louis Armstrong ballad La Vie En Rose. To view our world with rose-colored glasses fills the soul with happiness. To see the vibrance of all life on this planet takes these special French glasses, perhaps more special than a pair of Vuarnets. When Louis was singing this song he wasn’t privileged enough to eat where he wanted or to use the water closet where he wanted. He had to live life in Pink to keep smiling.

She also is dedicating this work to her love for the late Faith Ringgold and the colorful painter Kerry James Marshall. This exhibit is worth the visit to Jeffrey Deitch Gallery to see this iconic artist’s first west-coast show.

Hold Me Close, Bisa Butler

Jeffrey Deitch Gallery

7000 Santa Monica Blvd.

West Hollywood, CA. 90038

September 13 – November 1, 2025