By Cory-LaNeave Jones

October 8, 2025

Light in the Dark

The air in San Diego in October always carries a kind of cinematic light — that bleached hush before the credits roll, the sound of the ocean murmuring like a projector in an old theater. The San Diego International Film Festival (SDIFF) arrives just then, at the hinge between heat and reflection, when the city seems most itself: restless, coastal, half in shadow. This is San Diego in October: a city bathed in halogen and LEDs, and shadow, bargaining with its own coastline for a moment of stillness.

For Tonya Mantooth, the festival’s longtime architect and curator, that honesty is the point. “Film,” she tells me, “is empathy in motion. It’s the one art form that demands you look through another’s eyes.” This year, SDIFF festival runs from October 15 to 19, 2025. Ms. Mantooth laughs as she describes “the calm before the cinematic storm.” — Festival participants will crowd into the theaters, strangers drawn by a promise that a well-told story will pierce the air between their synapses.

In that spirit, we begin.

Ms. Mantooth’s Compass: The Festival as Moral Frame

When I reached SDIFF’s CEO and artistic director, she greeted me with the hum of preparations: posters being mapped, schedules being re-worked. She speaks quickly, with intervals of silence, as though listening for a cut. Her vision for the SDIFF is both capacious and precise — ambitious in scale, rigorous in moral intention.

“The festival is a platform for unity. When I curate, I’m thinking — what can I program that brings people together and not divide them?”

And, later: “Sometimes silence is really where the emotional truth lives. When it’s not cluttered with a lot of dialogue, I think it naturally pulls the viewer in.

Her words carry the weight of curatorial faith: that aesthetic decisions can shape civic behavior, that the flicker of a frame might be a political act. She also frames her ambitions in educational terms. The Focus on Impact initiative, she says, is not an afterthought — it’s woven into the festival’s DNA. Short films, curated lessons, filmmaker interviews — all delivered to classrooms at no charge. “I interview the filmmaker, so it’s a full package for teachers,” she says: “We include a full curriculum with it — that way, a teacher can screen it, talk about it, and really engage.”

She imagines the festival as ritual: rites of projection, Q&A sessions, lounges turned confessional. In that interstice of intention and execution, we arrive at the heart of her curatorial decision-making. The festival’s ticketing, social events, red-carpet logistics — these are means to sustain the mission, not ends in themselves.

Ten main takeaways from my conversation with SDIFF’s CEO and Artistic Director Tonya Mantooth

- Education is front-and-center. Tonya frames the festival’s response to cuts in arts funding around the expansion of the Focus on Impact education program and a new digital film library and curriculum portal for teachers — short films plus lesson plans and filmmaker interviews — offered at no cost to schools.

- Short films were chosen purposely for classroom use. The portal privileges short-form cinema because teachers can screen and discuss it within class time; Tonya explains teachers get a full curriculum, activities, and interview footage to deepen classroom conversation.

- Film as a tool for civic empathy. Mantooth repeatedly returns to the festival’s role as a place to practice “respectful dialogue” about complex social issues. She says the festival programs films to “bring people together and not divide them.”

- Silence and the cinematic inheritance. Tonya describes moderating a silent-film series and what she learned: “silence is really where the emotional truth lives,” and the experience of watching silent features demonstrates film’s power beyond dialogue.

- Curatorial compass — contemporary risk-takers. She names Chloé Zhao, Greta Gerwig, Jordan Peele and others as modern directors whose bravery informs the festival’s taste — filmmakers who leave space for silence, risk formal choices, and center emotional truth.

- Festival as community architecture. Asked whether she is gardener, architect or priest, Tonya answers that she touches all three — building structures, cultivating a familial team culture, and creating rituals that become community identity.

- A time-capsule image. Tonya wants the festival remembered by a photograph of two women — a filmmaker from Ireland and a patron — deep in conversation in the festival lounge: “that is the essence of what I want people to feel when they’re at the festival.”

- A commitment to bringing foreign-language stories to local students. Tonya recounts teachers’ delight when students “forgot they were reading subtitles” and were instead transported into other cultures — a small but telling anecdote about pedagogy and empathy.

- Party with purpose. The festival’s social events — notably the Belly Up fundraiser — are both joyful nights and practical mechanisms to fund education programs. Tonya is explicit: fun helps sustain the mission.

- Programming that answers the moment. Tonya singles out Odd Fish (Iceland) as a title she feels “could not have been made nor received at any other moment than now” — a film about identity, transition, friendship, and self-acceptance that she believes speaks to contemporary life.

Between the beats of our conversation, I sense the festival as a semaphore: a series of signals meant to activate attention, to ask the public to pause and reconsider. And then the shift happens: Ms. Mantooth guides me deeper into how this civic forum speaks to classrooms — a hinge into Shane Schmeichel’s domain.

From Stage to Classroom: Shane Schmeichel, Senior Director of VAPA

Ms. Mantooth’s investment in education is more than conceptual — it’s collaborative. She insists SDIFF cannot do it alone. So I spoke with Shane Schmeichel, Senior Director of Visual & Performing Arts (VAPA) at San Diego Unified School District, whose role is to translate the festival’s civic promises into daily practice.

But first: the art competition, the hinge between screen and school. The Focus on Impact Student Art Competition is not a token gesture. It’s engineered to elevate student voices — giving them exhibition space, t-shirt prints, and a public audience. That contest sits at the confluence of the festival and the school district’s arts machinery.

So when I spoke with Shane, I already had sense of how the two institutions — festival and school district — breathe in dialogue.

On the Mechanics of Student Art and Emotional Reach

In the VAPA offices, hallways hum with the quiet energy of curriculum planners, teachers, and art carts. Shane is deliberate, steady, matter-of-fact. But within his facts are small combustions of hope.

He describes how VAPA spans over 300 staff across 175 schools, reaching close to 95,000 students. The shared curriculum with SDIFF ensures that the short-film packages reach all corners of the district. Film becomes not a guest but a threaded cord in ELA, history, science — a method to spark inquiry across disciplines.

He emphasizes scale and access: the festival’s portal gives “access to all”, not just the elite few. The art competition, he says, isn’t simply about winning:

“Who cares if they win first place? If a kid was able to talk about racism or trans rights or whatever the social issue is — that (is) meaningful to them.”

“Our vision within VAPA is transforming lives through the arts.”

Under Shane’s watch, expressive arts therapy projects run in over 100 classrooms for six weeks, teaching social-emotional literacy via movement, drawing, and narrative. In one strand of the program, students who struggle with language find visual metaphors: a torn paper, a color clash, a layered collage.

In that sense, the festival’s ambition migrates from screening rooms into elementary classrooms. Tonya architects, Shane builds. Their partnership is not idealistic — it’s structural.

I left Shane’s space feeling the pulse of what festivals often promise but rarely deliver: a sustained opening for young minds — not just spectators, but participants. From there, the lens swings back out toward the spectacle looming on the horizon.

SDIFF 2025: A Festival with Ambition & Urgency

San Diego International Film Festival returns October 15–19, 2025, promising to be its biggest yet. Over 100 films, red-carpet events, panels, tributes, and educational programs fill the city’s theaters and public spaces.

The website emphasizes “red-carpet events, star-studded celebrations, and unforgettable experiences.” SDIFF schedules include the Night of the Stars Tribute (Thursday, Oct 16) at the Conrad Prebys Performing Arts Center in La Jolla. Social media teases a lineup across 29 countries and a global slate meant to provoke engagement beyond comfort zones.

This year’s Night of the Star’s pays tribute to several notable actors:

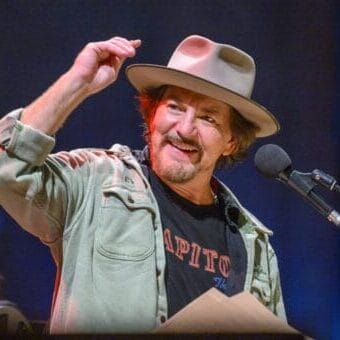

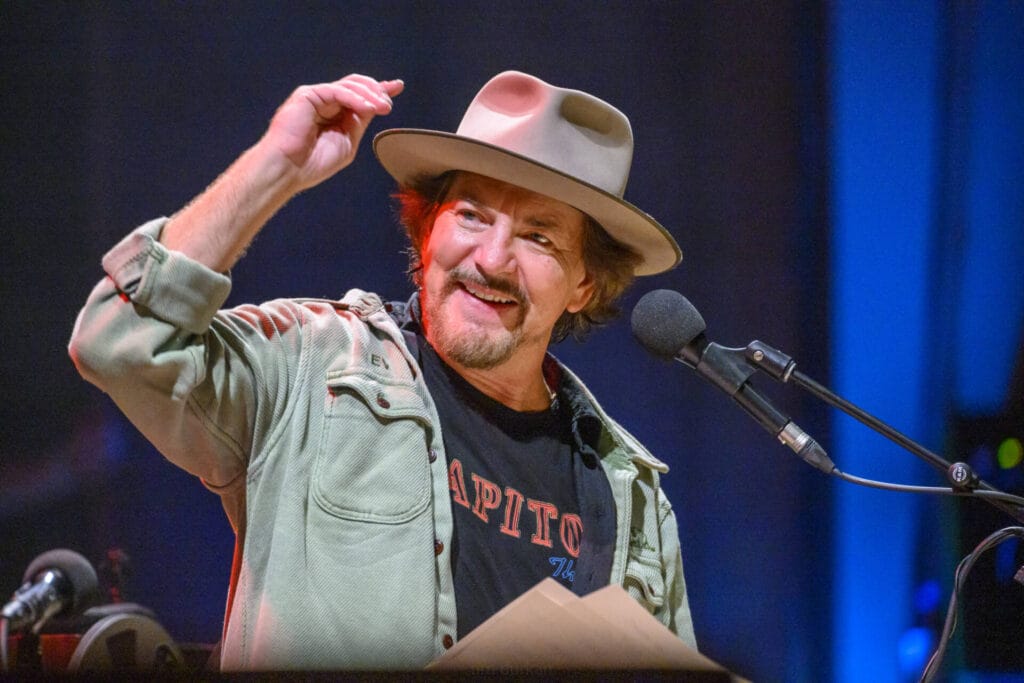

Mark Hamill, perhaps best known for his TV role played across from Gary Busy in The Texas Wheelers, also known for disco dancing with a weird flashlight in the 70’s and 80’s (i.e. This guy is Luke Skywalker from the original three Star Wars films). Hamill will be honored and force-ably given this year’s Gregory Peck Award for Cinematic Excellence. He has also joked around in a few animated comic TV shows shrouded in dark nights (i.e. he played The Joker in Batman).

John Magaro receives the Virtuoso Award. Best known for critical hit movies like The Big Short and Carol as well as TV programs, such as Orange Is the New Black and The Umbrella Academy.

Marlee Matlin receives the Visionary Impact Award. Known for portraying deaf people as she has not heard the what-for since 18 months old. She has been in too many movies and TV shows to name and in her free time is devoted to advocating for Easter Seals, Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, VSA arts, and the Red Cross. She has testified before the Senate to establish the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders.

Joe Manganiello receives the Spotlight Award. He is known for his roles in hit TV shows like True Blood, and epic dance movies like Magic Mike.

The festival describes itself as “more than just a film festival; it’s a cultural experience set against the stunning backdrop of California’s coastline.”

In practice, the programming is multifaceted:

- A studio premiere and independent-feature tier, where filmmakers arrive and discuss their work.

- Six short-film programs, each about 1.5 hours long and composed of six to eight short films. The festival site describes the shorts track in exactly those terms: “six short film programs (each program is comprised of approximately eight short films and runs 1.5 hours).”

“Sometimes silence is really where the emotional truth lives. When it’s not cluttered with a lot of dialogue, I think it naturally pulls the viewer in.” – Tony Mantooth

- Thematic categories: Social Impact, Women in Film, American Indian Cinema, Military stories, animation, student films, and local San Diego work.

- A Women’s Film Series extension, panels, networking events, a gala Opening Night, and social mixers.

- The Belly Up gala and fundraiser, which Tonya regards as essential to sustaining the festival’s educational mission.

Let me pitch it plainly: If you have even one evening to spare this October, the SDIFF is not a distraction — it is an excavation. A chance to see the world from corners you might never journey to, to feel that slow burn of new empathy, to remember how it feels to watch in the dark with strangers.

In a climate when time is the most precious currency, a single screening — perhaps Odd Fish, perhaps one of the curated short blocks — is enough to anchor you back into attention. The social events, the panels, the after-screening conversations — these are the bonuses, the outer glow to the central filmic core.

I asked Ms. Manthooth what she hopes from this year’s SDIFF could be preserved in a time capsule?

“It was a filmmaker who arrived from Ireland… and they embarked on probably a two hour conversation. And to me, that is the essence of what I want people to feel when they’re at the festival.”

Epic conversations about our storied lives.

Closure: Poetry in the Projector Light

The San Diego International Film Festival is, in essence, a microcosm of global cinema planted on our coast.

For Tonya, it is ritual and architecture; for Shane, it is a pipe through which the district’s students inhale the world. Both insist the point is not prestige but practice: practice in listening, in reckoning, in becoming citizens by learning to see each other more clearly. In a city that measures itself by sun and harbor, SDIFF insists, gently and insistently, that our common life might be mapped by images we allow to haunt us — the two-hour conversation in the lounge, the child who sees their life mirrored in a painting on a shirt, the classroom that forgets subtitles and remembers humanity.

I want to leave you — and the festival — with an echo from cinema’s older poetry: Luigi Pirandello once wrote, “The cinema should be closer to poetry than to theater.”

Time is taut in these five nights. So are memory and intention. Walk into a darkened theater, let your breath slow down, let the reel spin, and listen — perhaps you’ll hear your own story inside someone else’s frame.

SDIFF is being presented opening night at The Lot in La Jolla at 7611 Fay Avenue, 92037, and all of the remainder movies are shown at AMC Theaters at Westfield UTC located at 4425 La Jolla Village Drive, Suite H-60, San Diego, CA 92122.

BONUS INTERVIEW:

Vanguard Culture correspondent Cory LaNeave Jones interviews Academy Award® winner Marlee Matlin ( Children of a Lesser God, CODA ) at the 2025 San Diego International Film Festival: A Celebration of Cinematic Excellence, where she was honored with the Visionary Impact Award for her groundbreaking contributions to film and her tireless advocacy for inclusion. In her interview, Matlin reflected on her 40-year career and the importance of using her platform to create lasting change. She shared how, after the success of her debut film, she dedicated herself to championing closed captioning accessibility, advocating before Congress to ensure captions became standard on television — a change that now benefits people worldwide in hundreds of languages. Her enduring commitment to accessibility and representation continues to open doors for the Deaf and hard of hearing community, while enriching the art of storytelling for audiences everywhere.

– Video and summary by Anna Guillotte